By Aramís Castro, Nelly Luna Amancio and Gianfranco Huamán

A shihuahuaco tree can take 1,200 years to reach a diameter of 120 centimeters and a height of 50 meters. On its high branches, species such as the harpy eagle or scarlet macaw build their nests. Like other leafy trees growing in the thick Amazon, they capture huge amounts of carbon and feed mammals that contribute to ecosystem balance. Scientists, who have recommended its inclusion in the list of threatened species, estimate that each year, in Peru alone, approximately 184 thousand of these shihuahuaco trees are felled, which the wood industry then converts into parquet, polished wood or lumber to be exported to China (71%), Europe (13%), United States (7.5%), Mexico (3%) and other countries (5%).

Between 2001 and 2010, the volumes of shihuahuaco extracted from the Amazon forests of Peru were 10 times higher than what was cut in 2000; and in 2013, the extraction soared: it was 22 times higher than in 2000. The growing international demand for this wood resulted in increased pressure on the species.

Where does shihuahuaco wood cut or processed as parquet end and who are the main buyers? The answer is not simple, because the export information from the Peruvian Customs (SUNAT) does not contain details on the type of species or the scientific name of the wood pieces in all exported batches. It is not mandatory for the exporter.

HALF THE VALUE OF THE WOOD THAT PERU EXPORTS CORRESPONDS TO THE SHIHUAHUACO, REVEALS A PRELIMINARY ANALYSIS OF OJOPÚBLICO.

For this journalistic investigation, part of the Madera sin Rastro series, the eight-year information (2012-2020) of all export records mentioning the common names (shihuahuaco or cumaru) or the scientific names of the different species of the genus dypterix (or coumarouna). associated with this tree was organized. Shihuahuaco appeared in a total of two thousand shipments.

According to this preliminary analysis, as with other forest species, China is the main export destination. However, the lack of clarity in the data makes it difficult to know the final buyers of this timber and to follow the supply chain properly.

The European Union is the second importer of this timber extracted from the Peruvian Amazon, with 13%. Unlike exports of this and other tropical timber from Peru to the United States and Mexico, which declined after the ‘Yacu Kallpa’ case, Europeans have continued to buy shihuahuaco at the same rate in recent years. The main destinations - within this 13% - are France (49%), Belgium (14%), Denmark (13%) and others (24%). Here, shihuahuaco is known with the trade name of cumaru.

Between 2012 and October 2020, Peru exported more than 948 thousand metric tons of wood to the world for a FOB value (excluding taxes and insurance) of US$ 955 million. Of this total, more than half (at least 531 thousand tons) were in shihuahuaco, with a FOB value over US$ 531 million. That is, of all the wood that Peru exported, at least half corresponded to different species of the genus dipteryx (or coumarouna), shihuahuaco or cumaru, according to the data analyzed.

For this research, it was arranged with a group of forestry experts to develop the methodology and to create a log of scientific names (genera and species) attributed to shihuahuaco.

From the Amazon to European Furniture

Exports to the European Union between 2012 and 2020 amounted, from the data analyzed for this research, to US$ 68.4 million. Wood entered the old continent through 66 ports, mainly Le Havre, in France and Rotterdam, in the Netherlands. Although SUNAT's export information is incomplete, we found shihuahuaco wood buyers based in France, Belgium, Denmark and the Netherlands, among other countries.

Why is it important to know the business path of this tree? Since 2015, researchers have been alerting us that the growing demand for shihuahuaco wood has put the tree on the verge of extinction. They have warned that if no measures are taken to control its overexploitation in the Amazon, this millenary species could disappear. The association of logging companies is opposed to including this in the official list of threatened species.

THREAT. In Perú, approximately 184,000 shihuahuaco trees are cut down each year.

Picture: EIA

One of the final buyers of Amazonian timber is the Dutch-based Van Den Berg Hardhout company, which, according to its website, has a certificate from the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), an international forest certification which, according to the organization, guarantees that the wood purchased comes from forests with sustainable forest management. Throughout 8 years, Van Den Berg Hardhout imported more than 5,800 tons of Peruvian shihuahuaco valued at US$ 4.6 million.

In their online catalog they explain that cumaru, as they call the shihuahuaco they sell, comes from tropical forests of South America, “in the Amazon region of Brazil.” There is no mention of Peru, although export data indicate that Peru is one of its suppliers.

EACH YEAR, IN PERU ONLY, APPROXIMATELY 184 THOUSAND OF THESE SHIHUAHUACO TREES ARE CUT.

Consulted on the subject, company spokesmen confirmed to OjoPúblico, via e-mail, that about half of its imports come from Peru. They also explained that shihuahuaco was one of their “preferred” species because of its durability and resistance to humid conditions, such as those in the Netherlands. Van Den Berg Hardhout's representative also mentioned being unaware of the overexploitation of the tree, reported in recent years by scientists.

When asked about how they guaranteed the legal origin of timber imported from Peru, the company said that they only buy FSC-certified timber, that they comply with the European regulation for timber trade and that they keep “long-term relationships with fixed suppliers.”

The Dutch company suggested that we contacted Jeroen Ex, a Dutch forestry expert based in the Amazon region of Loreto, who, they said, contacted them with “the right suppliers in Peru.” Jeroen Ex worked as a specialist in timber acquisition in Inversiones La Oroza between April and October 2017, and since then he has worked as an associate consultant in ecosystem services in Form International. OjoPúblico tried to contact him by phone, but he did not take our calls, messages or emails.

The second European company with the largest imports from Peru in 2012-2020 is Vogel, based in Belgium. During this time, the company bought 2,700 tons of shihuahuaco for US$4.1 million from Peruvian companies such as Consorcio Maderero SAC, Industrial Forestal Huayruro and Maderera Bozovich. OjoPúblico contacted Vogel to find out how they secure the legal origin of the wood, but they did not answer the emails.

The third is Global Timber, from Denmark. This company claims to have “the greatest amount of wood in all of northern Europe [...] of the best quality, coming from six continents”. Customs records indicate that this company imported more than 2,200 tons of shihuahuaco from Peru, for US$3.9 million in these eight years.

The Danish company's catalog details that its products are made from cumaru from Brazil, but no reference is made to wood from Peru. Although this media tried to contact its representatives, they did not attend to our queries.

SINCE 2015, DIVERSE RESEARCHERS HAVE BEEN WARNING HOW THE GROWING DEMAND FOR SHIHUAHUACO HAS PUT IT AT RISK OF EXTINCTION.

The European Union, made up of 27 countries, is governed by the so-called timber regulation, which sets obligations for agents marketing this forest product and its derivatives. One of them is the need for wood to be supported by information on compliance with national laws is outstanding in order to avoid trade from illegal logging.

However, various specialists warn that to date there is no control due to products entering the continent.

“There are thousands of ways to defraud the authorities, such as getting irregular permits or misdeclaring wood species,” Klaus Schenk, director of Spain-based Salva La Selva , told OjoPúblico, via email. "These manipulations are not easy for European authorities to detect, because the wood comes with ‘legal’ permits. Another issue is the lack of controls in countries such as Spain, Italy, and Germany, where few inspections are carried out and few samples are taken.”

Peruvian Suppliers

In Peru, more than 60 companies are shihuahuaco's major exporters to the world. Putting the eight-year shipments (2012-2020) together, the first exporter of this timber to the European Union has been Maderera Bozovich, with exports of 6,500 tons to 20 European companies, for US$10.7 million FOB.

The second one is IMK Maderas SAC, for US$ 8.5 million FOB and it had as its main destinations to France, Belgium and Denmark. This Lima-based company began operations in 2004. The third largest export of this species is E & J Matthei Maderas del Peru, legally represented by Jorge Luis Valentín Budge Roca. In the last eight years, this company sent 5,100 tons of shihuahuaco to Europe, for US$6.8 million FOB.

In May 2017, one of its containers, destined for the Netherlands, was intervened by the anti-drug police. Among the wood, reported as shihuahuaco, more than 138 kilos of cocaine hydrochloride were found hidden. Sources from the Office of the Attorney General told OjoPúblico that the investigation into this case is being conducted by the Second State Attorney's Office with jurisdiction over illegal drug trafficking offenses of Callao.

Jorge Luis Budge Roca is also the legal representative of the Agroindustrial Jae SAC, a Sawmill sanctioned with more than S/9,800 by the National Forest and Wildlife Service (SERFOR) in 2019, for keeping forest products extracted without authorization at the time of the intervention.

OjoPúblico contacted the company’s representative, but until the close of this publication, they had not responded.

The Industry Opposition

What measures has the State considered to protect the growing commercial pressure on shihuahuaco? So far very few.

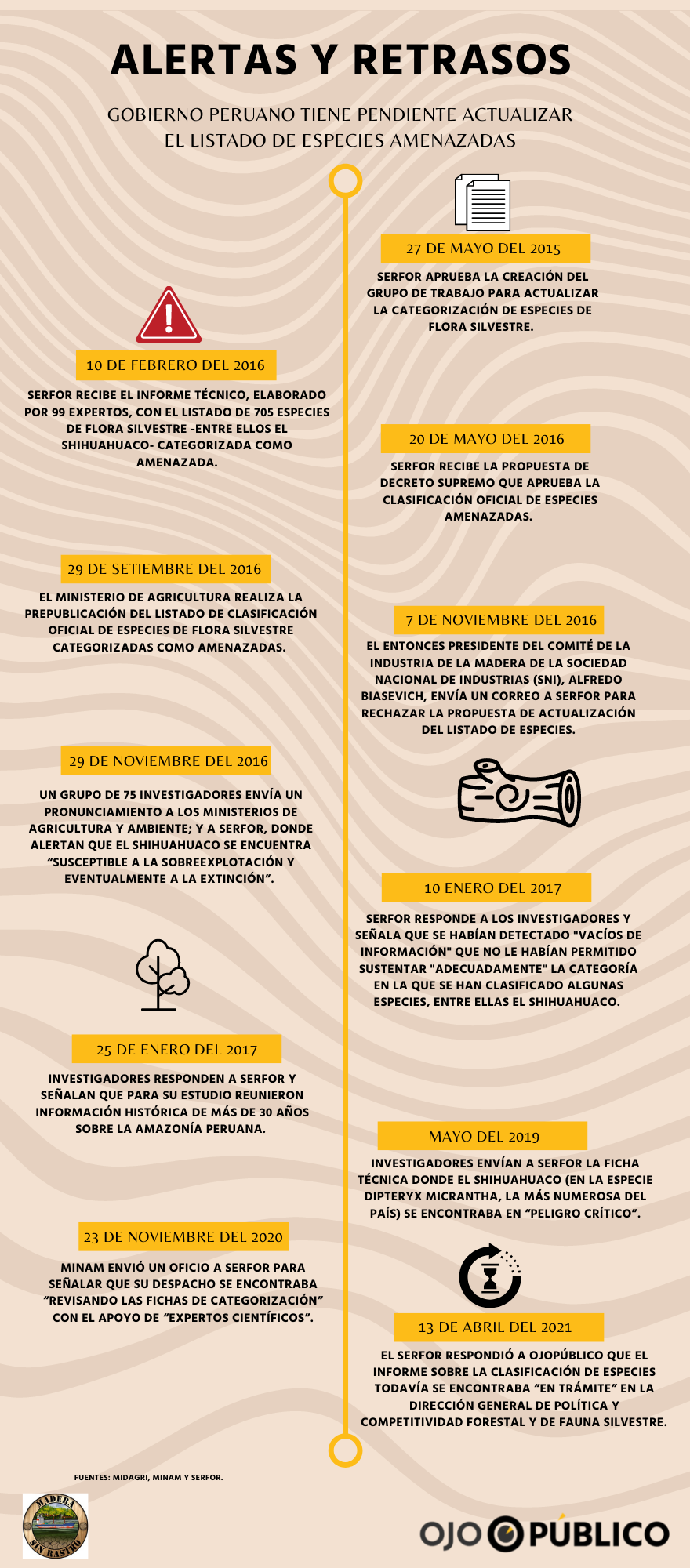

The first categorization of endangered species of wild flora was given in 2006 through Supreme Decree 043 and included mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla), cedar (Cedrela lilloi C.DC) and ishpingo (Amburana cearensis), among others. In addition, Article 138 stated that this classification should be updated every four years. However, since that first list there has never been any other change. The first attempt was in 2015.

VAN DEN BERG HARDHOUT IMPORTED IN EIGHT YEARS MORE THAN 5,800 TONS OF PERUVIAN SHIHUAHUACO VALUED AT US $ 4.6 MILLION.

In 2015, a group of 99 experts, were invited by SERFOR, under the supervision of the Ministry of the Environment, to analyze the situation of forest species and prepare a new list of endangered species. The list included 705 species, including shihuahuaco (Dipteryx micrantha). The report recommended classifying 61 species “in critical condition” and 87 “in danger”. With this technical report, the Ministry of Agriculture submitted its recommendations for public consultation, and it was then that the letters of the logging sector arrived.

On November 6, 2016, after the pre-publication of the list of threatened species, the Chairman of the National Society of Industries’ timber committee, Dr. Alfredo Biasevich Barreto, sent an e-mail, to which OjoPúblico had access , to different sectors of the State and the business sector. In the message, Biasevich rejected the inclusion of shihuahuaco in the list of endangered species and even requested its removal from the list.

“The timber industry is at risk, as virtually all timber species of high and medium commercial value are included,” Biasevich Barreto said in the email. He also criticized the classification proposed by Mauro Ríos Torres, whom he presented as a “well-known consultant in the forestry sector.”

STRUGGLE. Since 2015, scientists and specialists have recommended including the shihuahuaco within the list of threatened species.

Picture: Arbio Peru/ Gianella Espinosa

Ríos Torres, a forestry engineer, has had experience in the logging sector, where he was the manager of four companies that were closed, between 1998 and 2006, according to SUNAT records. In 2019 he also worked as an external consultant for Promogest SAC, an engineering and architecture firm. He is currently the director of sustainable forest heritage management at SERFOR, the institution in charge of approving, precisely, the list of endangered species.

On November 29, 2016, almost a month after the email communication from Biasevich Barreto, a group of 75 Peruvian researchers asked the Ministry of Agriculture to approve the list of threatened species “immediately” and to “take the necessary measures for the protection and recovery of wild populations of shihuahuaco species in the country”.

At the request of the scientists, SERFOR replied with a letter, sent on 10 January 2017. In this report, the forest authority argued that “gaps in information” had been identified in the categorization process which did not support the classification of some species. The document, signed by Walter Nalvarte from the Directorate for Sustainable Management of Forest Development and Wildlife, further indicated that the study had not conducted a population analysis of the species, although this evaluation should be carried out by SERFOR.

Two weeks later, on January 25, 2017, the researchers answered the letter and stated that the study organized and analyzed information from more than 30 years, in addition to comparing it with data from the official forestry yearbooks of the Ministry of Agriculture. Since then, SERFOR has not responded again.

However, in May 2019, a group of researchers sent SERFOR the technical file -to which OjoPúblico had access, indicating that shihuahuaco (as the species dipteryx micrantha, the most numerous in the country) was in “critical danger”, i.e. when they face an extremely high risk of extinction in the immediate future. Two years later, SERFOR has not approved the document yet, despite overexploitation alerts.

SEVERAL SPECIALISTS ALERT THAT TO DATE THERE IS NO CONTROL DUE TO THE PRODUCTS ENTERING THE EUROPEAN CONTINENT.

Almost five years after the pre-publication of the technical report prepared by the scientists, there are still no clear answers from the Ministry of Agriculture, a body in charge of the protection of forest management in Peru.

For six months, OjoPúblico insistently asked the authorities about the progress of the proposal, but only obtained an official response from SERFOR after making a request for information based on the Transparency Act. At the beginning of April 2021, the area responsible for the access to information indicated that the document was “in process” in the Directorate General for Forest and Wildlife Policy and Competitiveness, so it could not be delivered through “access to public information”.

DELAY. For six years the environmental authorities have still not included the shihuahuaco as a threatened species despite the great extraction of this ancient tree in the Amazon.

Graphic: OjoPúblico

The proposal has not yet been scheduled for publication, as the Director of Sustainable Conservation of Ecosystems and Species of the Ministry of the Environment, Fabiola Núñez Neyra, has reported in recent days. “There is a work of categorization that SERFOR is carrying out and we hope that it will soon be approved,” she expressed during the presentation of the digital book “Estado situacional del género Cedrela en el Perú” (Situation of genus Cedrela in Peru), without giving further details.

On April 22, SERFOR biologist and specialist, Rosario Bravo Urroto, also referred to the topic in an academic activity and indicated that the document was “in process”. However, this specialist anticipated that shihuahuaco appeared on the new list, without mentioning the degree of threat in which two of its species were considered: dipteryx micrantha and dipteryx charapilla. That is to say, she did not explain whether they are in critical danger, endangered, in vulnerable situation; or whether they qualify as almost threatened or with insufficient data to determine a specific category.

This meeting was part of a research project conducted by the National University of San Cristobal de Huamanga and a group of Brazilian scientists. The aim of the work is to gather information to allow the conservation of shihuahuaco, considered in the study as “a threatened neotropical species”.

When asked about the delay in the approval of this document, the former SERFOR chief, Luis Alberto Gonzales-Zúñiga, said that when he was in office - between February 2019 and June 2020 - they tried to move forward “discreetly because it would generate resistance on lumber exporters.” Gonzales-Zuñiga added that they did not have enough funds to complete the process, which was in charge of SERFOR’s heritage management direction and that it needed to be “solid enough for no one to object [the results].”

Last year, the Peruvian government removed Gonzales-Zúñiga from office without prior notice, while this sector was pushing for measures against lumber trafficking. “There was an underground and dark job to weaken us,” the former forestry official said in an interview with this media, after his disengagement.

In the face of OjoPúblico consultations , SERFOR avoided expressing an opinion on the approval of the new categorization of threatened species, and indicated, through its press office, that they could not “give any information until [the listing] is published”.

A MINAM representative, meanwhile, said they had been involved in the process since 2014, and that the last official communication with SERFOR took place in 2020. However, they indicated that the technical teams in the sector “have been coordinating”. The communications area also explained that, to date, two species listing proposals have been received: One prepared in 2018 and the other in October 2020.

The approval of this standard has not been the only pending task for the forestry sector: when analyzing the historical exports of shihuahuaco, OjoPúblico also detected inconsistencies in the scientific classification attributed to this tree -of genus Dipteryx- in the last two official lists of forest products , which are in charge of SERFOR.

According to the forestry authority, in 2016, the Peruvian Amazon Research Institute (IIAP) performed a review showing the existence of Dipteryx micrantha and Dipteryx charapilla in Loreto. While the presence of other species of genus Dipteryx previously identified in Peru, such as Odorata, alata and rosea, was discarded by the authors of the study.

The institution indicated that the changes in the technical documents was because “certain species are under a taxonomic review process, which is shown in changes in the existing scientific names, as well as in their presence in the country”.

The discussion and relevance of these nomenclatures goes beyond the scientific sphere: the way shihuahuaco is identified when officially included in the list of threatened species will depend on them.

Alerts about the possible extinction of shihuahuaco, as well as the little information about this species, area reality not only in Peru. The doctor in tropical botany from the Botanical Garden Research Institute of Rio de Janeiro, Catarina Silva de Carvalho, indicates that in Brazil, the “lack of knowledge related to the delimitation of species and the actual size of the population” of this tree are some of the reasons why its conservation is a priority.

Silva de Carvalho also believes that this species should be included in the list of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), but first proposes to publish a taxonomic study outlining the species in the genus. “Another step I think can be taken is investment in science, to conduct studies on the population, ecology, and conservation of species being exploited,” she added.

In early May, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) collected findings from a study by Silva de Carvalho, and other forest researchers, to support and recommend that genus Dipteryx, including the Peruvian shihuahuaco, be included in the CITES list.

Tienes reportajes guardados

Tienes reportajes guardados