A group of transnational laboratories in Peru has for 17 years enjoyed special benefits on the importation and sale of drugs that treat cancer, HIV and diabetes: on entering the country, the medications are exempted from a 6% tariff and are subsequently exempt from the 18% sales tax.

The objective was to help patients by reducing the high cost of their treatment. However, studies conducted between 2010 and 2012 by civil society organizations and the Ministry of Health (MINSA) show that whilst prices did not fall at the rates anticipated, in the case of anti-cancer drugs the profit margins of pharmaceutical companies increased by up to 64%.

The benefits have nonetheless remained in place. Indeed, the number of tax-free medicines has increased. Ojo-Publico.com gathered information from the National Superintendency of Tax Administration (SUNAT), the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) and the Customs Office to calculate how much these exemptions cost the state. We discovered that between 2001 and the end of 2017 at least PEN 648 million was forgone by the state through these tax exemptions to pharmaceutical companies that import products for cancer, HIV and diabetes.

The uncollected sum could have funded the entire treatment costs of 17,588 women with advanced breast cancer given the exorbitant prices for these high-demand drugs. One such medication is Trastuzumab, produced by the Swiss transnational Roche and sold for PEN 5,210 per dose as Herceptin. Other large companies that benefit from these tax exemptions include Merck, headquartered in Germany, and subsidiaries of the US companies Johnson & Johnson, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Eli Lilly.

The exemptions estimate is taken from technical reports provided by SUNAT to MEF between 2005 and 2017, to which Ojo-Publico.com gained access, complemented by the annual medicine import figures registered in the Single Customs Declarations (DUA is the Spanish acronym). For cancer and HIV medications, our figures cover the period 2001 to 2013.

Given that the Customs Office import registry shows tax savings to pharmaceutical companies between 2005 and 2013 of PEN 304,000,086 on medicines to fight cancer and HIV, the MEF’s figure of PEN 329,000,961 seems conservative given that it also includes high-cost diabetes medications.

The products in greatest demand to treat these diseases are known as biological or biopharmaceutical products because they are created from living organisms rather than chemical synthesis. Their use is restricted. Rather than being provided by pharmacies, they are sold directly to the state through ESSALUD, MINSA, the armed forces and the National Police. The manufacturers and suppliers set their own prices and face almost no competition.

ONCOLOGY. One medication in high demand is Trastuzumab, produced by the Swiss transnational Roche and sold for PEN 5,210 per dose as Herceptin.

Photo: Getty Images

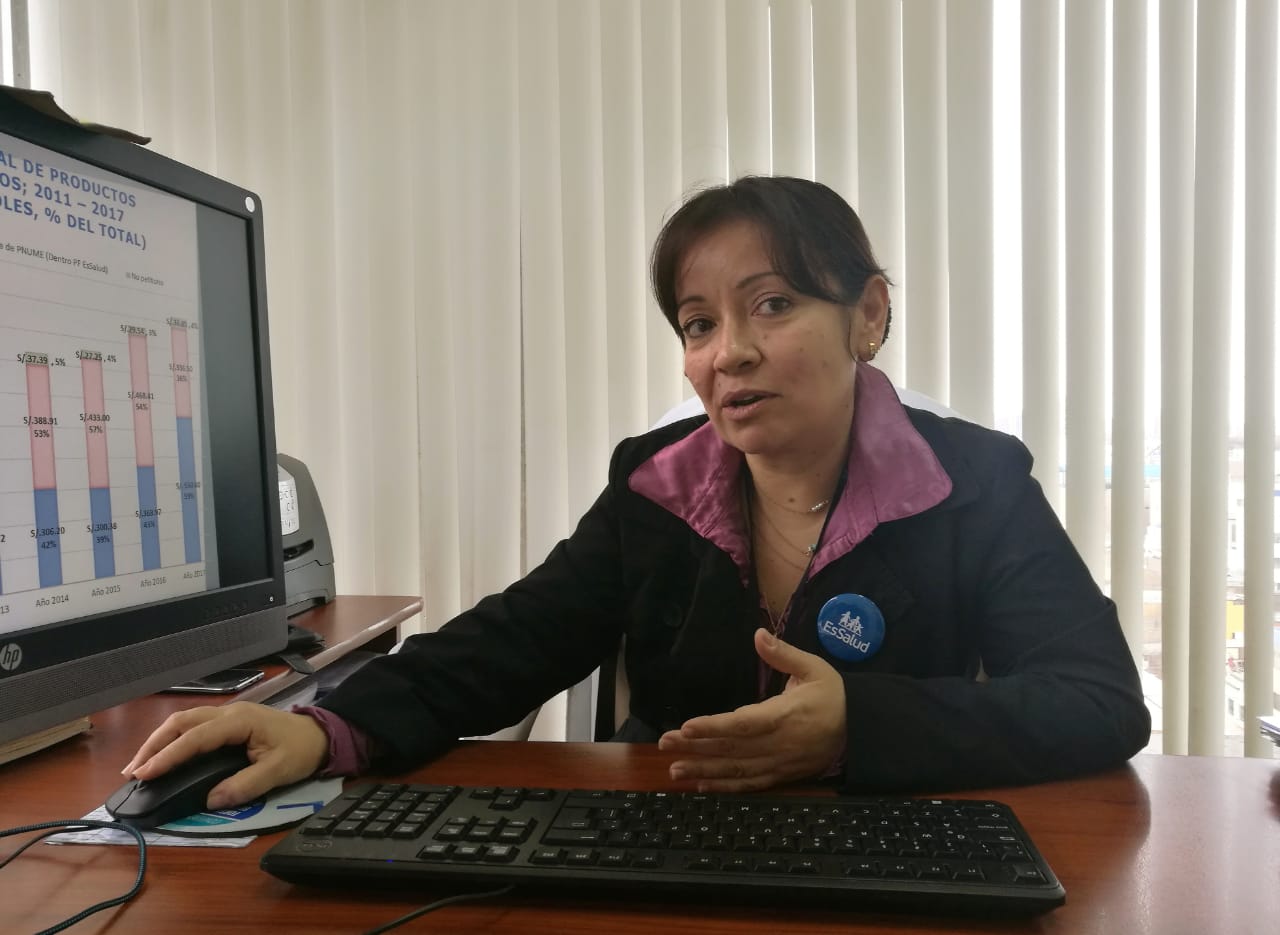

Patricia Pimentel, Director of the ESSALUD Institute for Health and Research Technology Assessment (IETSI is the Spanish acronym) argues that at least 60% of the biological medicines entering the country to treat cancer do so under monopoly conditions, a situation that is an impediment to lower prices.

“We buy 70% of the biological drugs prescribed for cancer and we can state that the exemption has not been transferred to the patient and in our case has not generated savings for the institution. If anyone has benefited, it has been the supplier or the industry itself, but not the patients or the state,” she said.

More exempted medications

These tax benefits began on November 21, 2000, whilst the country was distracted by the impeachment of the then President Alberto Fujimori. The opposition APRA party sponsored a bill promising to reduce costs of treatment of cancer and HIV in exchange for the tax exemption, but did so without any technical study into the effectiveness or economic impact of the proposal.

With the debate overshadowed by the political situation, the plenary approved the bill in just five weeks. Although the executive branch questioned the bill, in May 2001, Congress passed it as Law 27450. Four years later, and again in the absence of technical studies, Congress passed Law 28553 that added drugs against diabetes.

The laws created an unrestricted tax benefit that favored the laboratories. Unlike a typical tax exemption that is in theory temporary and must be ratified from time to time by the legislative branch, laws 27450 and 28553 each specify that the medicines are never to be affected by the imposition of tariffs or the collection of sales tax. The laws also require MINSA to approve the list of drugs and supplies that will be released from taxes and request that these be “annually evaluated and updated so that the benefits are passed on to the population.”

Currently, 124 active substances for cancer treatment are exempt from the taxes, 31 for HIV treatment and 41 for diabetes. Over the years at least 12 lists have been published. These have gradually served to increase the number of exempted medicines. Similar efforts have not been made to evaluate whether the savings generated by these laws have been passed on to patients.

Ojo-Publico.com sought access to the file notes of the supreme decrees that broadened the list of exempted drugs. These documents had passed through various offices of MEF, MINSA, and the Presidency of the Council of Ministers (PCM). They attach a list of medicines endorsed by the Directorate General of Medicines, Supplies and Drugs (DIGEMID), which is the governing body for the pharmaceuticals sector.

According to these documents, to introduce a high-cost drug tax free into the Peruvian market a laboratory need only meet four requirements: prove the drug’s health registration, confirm the use of the drug for treatment of the relevant disease, provide an opinion about the drug’s therapeutic qualities, and; demonstrate that the drug contains new active pharmaceutical ingredients whilst applying the associated name.

The evaluation process applied by government departments was limited to financial calculations about the prospective impact on the state’s coffers. For example, file notes to Supreme Decree 023-2016, which authorized the inclusion of 33 anti-cancer and HIV drugs on the tax exemption list, indicated that the state would cease to collect PEN 6.63 billion. The law was passed without alteration.

Across all the documentation there is just a single reference to patients: “The list of medicines and / or supplies must be updated so that the benefits reach those suffering these diseases in order to improve their health and quality of life. Above all, for those with fewer resources.” Nowhere is it explained how this might be accomplished.

ESSALUD re-evaluated the anti-cancer drugs that appear on the exempt list as recently as 2018. It found that six of them were either not safe or were ineffective for some diseases or under certain conditions. Cetuximab, from the Merck laboratory, is one such drug. ESSALUD has ruled it out as a treatment for recurrent head and neck cancer. The scientific studies supporting the approval or rejection of these drugs appear on the IETSI website. They are also available to MINSA following the signature of a recent agreement.

“DIGEMID is an entity that authorizes sales and enforces security, but not efficiency. In ESSALUD we have differentiated those drugs that are not effective or safe for specific cases. We have not even seen if they are cost-effective, that is, if recovery rates justify the price, but at some point we have to undertake this analysis in Peru to decide what we buy and what we do not,” explains Pimentel.

Javier Llamoza, a researcher at Acción Internacional para la Salud (AIS), agrees that the tax exemption on medicines should include the effectiveness factor. To do otherwise is to favor lower impact drugs compared to others already circulating in the market at a better price. “Tax exemption is an incomplete mechanism unless efficiency is analyzed and the market is opened to other bidders, because the decision on whether to reduce or inflate costs is in hands of the company,” he said.

Last June, DIGEMID’s Directorate of Pharmaceutical Products launched a public consultation as part of the authorization process for a new list, this time with 22 anti-cancer drugs and three additional antiretroviral drugs.

WARNING. Patricia Pimentel, Director of ESSALUD’s Institute for Health and Research Technology Assessment (IETSI), says that the anti-cancer drugs that appear on the tax-exempt list were evaluated and some were found to be unsafe or ineffective.

Photo: Elizabeth Salazar

Ghost Commission

Ten years after the first law was passed, studies by AIS and RedGE confirmed the inefficiency of the exemptions. In response to the media scandal that was generated at the time, the government of Alan García created a multisectoral commission responsible for monitoring the impact on cancer and HIV patients.

According to Supreme Decree 004-2011, the membership consists of representatives of the deputy ministries of health and economy, as well as officials of INDECOPI and SUNAT. The commission must “report annually” to MEF “the impact of the exemptions to verify if the benefits have been passed on to the population, and take action as appropriate”. Seven years have passed and none of these reports has been made public. According to the PCM website, the commission’s last recorded activity was in October 2017.

Anonymous sources said that the commission meets once or twice per year to analyze the financial impact of the taxation privileges but lacks the power to request price information from insurance companies and private clinics. The sources could not recall any joint report to re-evaluate the exemptions, and said that the purpose of the commission’s meetings in fact to endorse new lists of exemptions recommended by DIGEMID.

We unsuccessfully sought interviews with INDECOPI, MEF, MINSA and SUNAT personnel to find out their specific role on the commission.

The monopoly of transnational companies that sell biopharmaceuticals is supported by intellectual property rights (patents) obtained over a period of time to protect their formula, and also by criminal and administrative penalties that they encourage against competition. As reported by Ojo-Publico.com, either individually or through the National Association of Pharmaceutical Laboratories (ALAFARPE is the Spanish acronym), laboratories have tried to block the entry of biosimilar medicines that are cheaper versions of their products.

We have been seeking an interview with an ALAFARPE representative for three weeks without success. DIGEMID has also chosen not to comment. We were able, however, to obtain had access to the aide-memoire that DIGEMID presented in April to the Consumer Protection Commission of the Congress during the debate on Bill 2371 that proposed to regulate the medication prices.

In her presentation, DIGEMID Director Susana Vásquez demonstrated that joint purchases made by the state achieve better prices when there are several bidders. In such cases, the costs fall by between 28% and 57%. Where there is just a single supplier (as is the case with most cancer product suppliers), the reduction reaches a maximum of 5%. “Measures are needed to correct these distortions in the national pharmaceutical market through efficient regulatory mechanisms such as those developed in other countries,” said the official.

César Amaro, a pharmaceutical chemist and former head of DIGEMID, believes that the state should create a monopsony, that is, a monopoly on the part of the buyer which allows it to negotiate transparently with the companies to supply high-cost products in scarce-supply to all public institutions over a minimum one-year period using set rules. He also argues that the Fondo Intangible Solidario de Salud (Intangible Solidarity Health Fund) and the Centro Nacional de Abastecimiento de Recursos Estratégicos en Salud (National Center for the Supply of Strategic Resources in Health) should be given a cross-cutting role.

Last month the executive branch approved a law to allow international purchases of medicines. This, together with the law published in 2016 to allow the gradual entry of biosimilar drugs, could expand the market and generate competition among the owners of biological and high-cost products. It is likely be at least 2021 before we begin to see the entry of biosimilar products and only if no legal action is taken to delay the process.

Illustration: Francisco Muñante

Tienes reportajes guardados

Tienes reportajes guardados