Updated: July 8, 2021.

In December 2018, Colombian Environment Minister Ricardo Lozano received the international ‘carbon pricing champion’ award on behalf of his government, for promoting innovative economic solutions to curb the climate crisis.

That day, words of praise for Colombia flew in the Polish city of Katowice, where the annual United Nations conference on climate change was underway. Dirk Forrister, who was once Bill Clinton's climate advisor and now heads the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA), which awarded the prize, celebrated “yet another country using market mechanisms to advance the goals of the Paris Agreement”, which had been signed three years ago and which at last -after several resounding failures- paved the way for a new global consensus on how to solve the crisis before it becomes irreversible.

His colleague Margaret-Ann Splawn, director of the Climate Markets and Investment Association (CMIA) and also a patron of the prize, emphasized that the Colombian case shows how “how government policy is helping to drive technological advances, by incentivising innovation and investment in low-cost abatement projects”.

Colombia received the award for its pursuit of financial schemes that reduce the greenhouse gas emissions that we release into the atmosphere and drive climate change. They were particularly impressed by the innovative mechanism that the Colombian government unveiled in 2017, whereby private companies that must pay a carbon tax on the fossil fuels they consume can instead offset their emissions by supporting projects that encourage conservation.

One pillar of this strategy are Redd+ projects, which link local communities that are slowing deforestation with companies that want to neutralize their own carbon footprint. Few projects symbolize this commitment in Colombia -one of the nine countries that are home to the Amazon- like Matavén, a forested area in southern Vichada, in eastern Colombia, and on the edge of the Amazon, where almost 13,000 indigenous people are caring for the habitat where they live and selling carbon credits.

The data, however, suggests that Matavén -the largest of the more than 80 Redd+ projects listed in the Colombian government’s mitigation project database- could be promising much greater deforestation savings than it has actually been able to guarantee. This emerges from an analysis of official and project documents and a dozen interviews with scientists, public officials, consultants, researchers, diplomats and indigenous affairs specialists, many of whom requested anonymity to speak candidly about an issue viewed as sensitive within the environmental sector. Given the highly complex and technical nature of the carbon market, in addition to this reporting, we teamed up with Carbon Market Watch, a European non-profit organization specialized in monitoring carbon markets and verifying that they do indeed lead to low-carbon societies. Their report was also published today.

This reality means that many of the carbon credits being sold by the largest project of its kind in Colombia could be a mirage - what climate circles call ‘hot air’. Matavén’s potential incongruences highlight wider flaws in the system that regulates the country's carbon market, raising questions about how effective this system currently is in curbing deforestation in the Amazon.

These inconsistencies have a double economic impact for Colombia, which - as this investigation reveals – could be missing out on millions of dollars because these credits allow the companies that buy them to be exempt from paying the national carbon tax. At the same time, the Colombian government has been forced -in order to avoid double counting- to subtract these credits from the international aid funds it receives to halt deforestation in the Amazon, its main environmental commitment under the Paris Agreement and on which a significant part of its international reputation depends.

This blow to the Colombian State’s pockets shows why it would be a good investment for Colombia to strengthen its oversight over the carbon credit market that helped bring the award only three years ago, but which seems stills to be operating like a ‘wild west’.

AUTORITY. Environmente Minister Ricardo Lozano receives the Carbon Pricing Champion award.

Photo: Ieta.

A jungle between the Amazon and the Llanos

Matavén is, from two points of view, perfect for a Redd+ project.

On the one hand, it is a unique ecosystem in need of protection, serving as a transition between the jungles of the Amazon and the savannas of the Orinoquia in eastern Colombia. Framed by the Guaviare and Orinoco rivers, in the northern corner of the rocky outcrops of the Guiana Shield and around the basin of the stream giving it its name, the Matavén rainforest is of “special biological interest, not only for its biogeographical position, but also for its good state of conservation, with less than 5% of the total area transformed into cultivated areas and stubble,” concluded the Humboldt Institute, the main institution in charge of studying Colombian biodiversity.

It did so after, in 2009, 14 biologists and 11 indigenous research assistants traveled through its savannas and floodplain forests, its dry forests and its rocky outcrops, collecting animal and plant samples to produce the first characterization of Matavén’s biodiversity and one of the few that exist in Vichada.

After a second round of expeditions in 2016 and 2017, the Sinchi Institute of Amazonian Studies published the Matavén animal book, which lists –in both Spanish and the Piaroa language- the 206 species of birds, 72 mammals, 47 reptiles and 36 amphibians they found working in hand with some thirty indigenous persons. These numbers mean that this area alone is home to one out of every ten bird species in Colombia, in addition to 14 percent of the mammals and 6 percent of the reptiles.

On the other hand, the Matavén Jungle Unified Indigenous Reservation -located in the municipality of Cumaribo- is a rich ethnic mosaic where some 12,800 indigenous people from six Amazonian peoples live together. It is they -Sikuani, Piapoco, Piaroa, Puinave, Curripaco and Cubeo- who care for the 1.85 million hectares of a shared and veritably multicultural reserve. One of these groups, the Piaroa, are even considered at risk of physical and cultural extinction by the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC), as they only comprise 773 members on Colombian soil.

They did not always share this territory. Two decades ago, Matavén was a constellation of 16 independent reservations, with pockets of State-owned lands in between. Concerned about indiscriminate hunting and fishing, as well as news of the government's interest in eventual oil extraction, the indigenous communities began to organize to think about how to protect their territory and -with support from the Etnollano Foundation- created a single common authority to govern the reservation: the Association of Councils and Traditional Indigenous Authorities of the Matavén Forest, better known as Acatisema. In 2003, the now defunct Colombian Agrarian Reform Institute (Incora) created the current reservation, incorporating the existing ones and adding the land in the middle. Thus was born the ‘unified reservation’ that exists today and lies at the center of the Redd+ project.

Its ecological and social value is so clear that talks about creating a national park there advanced, seeking to copy the model used over the last decade in other protected areas -such as Yaigojé Apaporis National Park in the Amazon, Uramba Bahía Málaga on the Pacific Ocean or Acandí Playón Playona in the Caribbean- whose care is the responsibility of indigenous or Afro-descendant communities. “It is essential to protect these forests, which is why attempts to approach the indigenous communities were made. All the environmental arguments are there,” Julia Miranda, who was director of National Parks for 16 years and until the end of 2020, explained to this journalistic alliance.

The idea to create a national park, however, didn’t pan out and communities ended up opting for the Redd+ model. After a couple of failed attempts, the current project began to be discussed in 2012 and was finally validated five years later.

AMAZON. Aerial view of the Matavén reservation.

Foto: Fundación Etnollano

Money to not cut down the forest

Taking care of forests like those of Matavén has two great values to curb climate change: on the one hand, it prevents carbon from being released into the atmosphere when they are cut down and, on the other, it ensures that they continue to store carbon –‘sinking’ or ‘sequestering’ it, in environmental language- as well as guaranteeing that they continue to provide services such as drinking water, climate regulation or preventing the transmission of viruses such as the one that caused Covid-19.

Territories inhabited by indigenous communities are ideal for this type of project, since high-impact activities are usually banned inside them and because these groups are already in charge of their governance. Project Drawdown -which brought together more than 200 scientists from around the world- even considered indigenous land management as one of the 100 most effective solutions to curb climate change, with a potential to reduce 5.25 gigatons of carbon dioxide by 2050.

More than a decade ago, tropical countries like Papua New Guinea and Costa Rica began insisting in climate negotiations that forest conservation be recognized as a solution to the global crisis. Since conservation requires money, climate finance experts began to devise economic models that could make such efforts profitable - or at least sustainable.

One of them is the Redd+ mechanism, which was born in 2007 as a tangible financial incentive to reward communities that successfully avoid deforestation and allow them to turn that mission into a job. The idea is that the resources to maintain the conservation effort are provided by private companies seeking to offset the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions generated by their activities. Because they acknowledge their environmental footprint - or simply want to avoid paying taxes that penalize them for emitting those gases - they buy carbon credits that allow them to ‘neutralize’ their emissions. And as a market system, it can be more efficient and sustainable than simply granting subsidies.

In practical terms, they pay those who do not cut down forests.

Such schemes –which have been officially incorporated into the UN Climate Change Conventio- have become an invaluable source of income for many local communities living in areas prone to deforestation in tropical countries. Among other reasons, their attractiveness is due to the fact that one hectare of Amazonian rainforest can store 566 tons of carbon, so keeping it standing can yield the same volume in credits sold.

In total, there are 89 Redd+ projects in Colombia registered in Renare, the new Ministry of Environment database listing mitigation initiatives. However, it’s difficult to understand their current status, since the official government registry says –as of June 10th- that none are active yet. It does show four are awaiting approval, 26 are in formulation and 46 are in the feasibility stage. Among the latter is, paradoxically, Matavén, which nevertheless has been selling credits for at least four years.

In the long term, they can help countries like Colombia, which contributes a relatively low amount of greenhouse gases compared to other countries, to fulfill its single most important contribution to solving the climate crisis: to preserve as much of its forest cover as possible.

Especially in the Amazon, which is the largest continuous rainforest in the world, harbors two thirds of the country’s total forest cover and on whose margins Matavén is located.

The Matavén rainforest project

The Matavén Redd+ project began in January 2013 on 1.1 million hectares of the reservation, following an agreement signed six months before by the indigenous people gathered in Acatisema and the environmental consultancy firm Mediamos F&M that conceived it.

At least five companies have been linked. It was structured by Mediamos F&M, based in Cali and led by Francisco Quiroga Zea, a forestry engineer and former vice-president of the Universidad del Valle. It was certified by the US organization Verra with its Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), one of the most widely used in the world and designed “to ensure the credibility of emission reduction projects”. Its auditors, in charge of checking compliance with these rules and how many tons of CO2 they have avoided, were Colombian company Icontec and more recently the Indian consulting firm Epic Sustainability Services. Finally, the trader for part of its carbon credits has been Swiss consultancy South Pole.

Since 2017, Matavén has placed carbon credits on the market, corresponding to emission reductions since 2013, given that a project can credit them back into the past if it proves so. In total it foresees, according to its own projections, avoiding the release of 108.5 million tons of carbon dioxide over three decades of operation. In other words, some 3.6 million tons per year until December 2042, according to Verra's public record.

According to the project's own data, it already prevented the emission of 4.4 million tons of CO2 into the atmosphere in 2013, 8.7 million in 2014-15 and 7.5 million in 2016-17. Although there is no Colombian government registry of carbon credits buyers, companies such as Latam Airlines have publicized their support. In its 2019 public report, it listed it among three environmental projects with which it offset its national carbon footprint and in fact complaining about the scarcity of similar projects in the country. In 2020, however, it didn’t include Matavén among its offset projects, explaining that the pandemic slashed the airline’s emissions by more than half.

Seven companies that sell fuel through service stations are also listed as buyers of Matavén credits between 2018 and 2020, according to a July 2020 document on credit retirements on Verra's website.

Primax Colombia was the largest user with at least 5.2 million units in 2019. That same table also includes: Terpel with 1.6 million, Biomax with 1.45 million, Exxon Mobil with some 917.000, Chevron with 793.000, Petromil with 712.000 and Puma Energy -which only operates in the Caribbean- with 15.000. In addition to these, Ecopetrol -the state-owned oil company and the largest company in the country- used 74.000. Other minor buyers include Combustibles y Transportes Hernández -which sells fuels to the aviation sector- with 48.000 or the electrical panels manufacturer Energizar SAS with 7.500.

This alliance asked two of these companies, Primax Colombia and Latam, how they assess the quality of the carbon credits they purchase, knowing that they are the least able in the chain to verify their validity. Until this story was published, we had not received their responses.

FOREST. The Matavén reservation is located in the transition between the Amazon and the Orinoquia. Photo: Etnollano Foundation.

Foto: Fundación Etnollano.

Questions left by Matavén's calculations

All Redd+ projects revolve around two central questions: what would happen to an area worthy of conservation if it were left alone, with problems -such as illegal logging, uncontrolled colonization or extractive projects- that would result in its degradation? Can such a hypothetical scenario be avoided by paying inhabitants to ensure this does not happen?

The Redd+ model is based on being able to guess the most realistic deforestation trajectory in a natural area, which can be contrasted with the effort made by its inhabitants to avoid it. The difference between the two scenarios would be the impact of the project, measured in tons of carbon dioxide that will no longer be released into the atmosphere and then translated into credits traded on the market. That money should then go to the communities that care for them, as well as to the various companies –project developers, verifiers and brokers- that take those credits to their final purchaser.

The key question is how to correctly quantify these emissions savings. As it is very difficult to compare a hypothetical scenario with a real one, various methodologies to calculate it have been created by standards like Verra’s VCS that stamp their seal of quality. These generally focus on choosing an area that acts as a mirror for the future that could be, showing what might happen in the original one if deforestation were allowed to advance and no Redd+ project materialized.

That a project brings real environmental benefits depends on whether the second area chosen -which sets the baseline- does not present the worst imaginable outcome, but the most plausible one. If an area that is much better cared for is selected, the efforts of those who preserve the first one will not shine through. If, on the other hand, the area chosen has a much more accelerated deforestation trend, you end up with illusory greenhouse gas savings – something known as ‘hot air’ or ‘ghost credits’ in the industry.

For example, if a project anticipates that 1,000 hectares will be cut down in a given year without conservation efforts, and 800 hectares are actually cut down, the difference of 200 hectares is what it can present as a reduction in deforestation and translate, once converted into tons of carbon, into issued credits. But if that same project anticipates a deforestation of 4,000 hectares per year, it could show results for 3,200. The heart of the matter, then, lies in having a real calculation of the risk and not a much higher one.

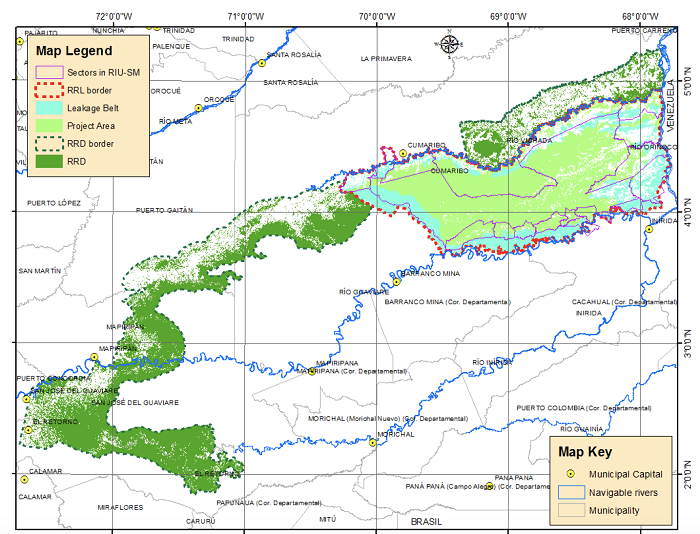

Despite the fact that the indigenous people of Matavén have been leading a worthwhile conservation effort, several questions arise around the area that their Redd+ project has chosen as a mirror: an elongated strip of about 1,4 million hectares that meanders -with one interruption- from the Orinoco River on the Venezuelan border to the east of San José del Guaviare, as its project design document (PDD) shows.

LANDS. In light green is the project area and in dark green is the reference area.

Image: Matavén PDD, taken from Renare.

The problem is that there are at there are significant differences in at least three key elements to understand the risk of deforestation in a given area, according to Carbon Market Watch’s months-long analysis.

First, while Matavén is a remote area that can only be reached by river or plane, the baseline incorporates an arc of Guaviare, Meta and Vichada that is better connected to the rest of the country and therefore more exposed to deforestation risks.

The early warning maps published by the Colombian Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies (Ideam) –Colombia’s meteorological agency- every quarter since 2013 seem to confirm this. Three areas located in the reference zone routinely appear as deforestation hotspots: northeast Guaviare, between San José and the Nukak indigenous reservation, has been considered an area of concern during the years from 2017 to 2020. The southernmost corner, corresponding to El Retorno in Guaviare, was highlighted each year from 2016 to 2020, with the exception of 2018. And the Mapiripán zone, in Meta and towards the middle of the reference arc, did so every year between 2017 and 2020. In contrast, the area where Matavén is located does not include hotspots on any occasion.

IMPACT. This map of deforestation hotspots, from the first quarter 2020 bulletin, shows the three areas -Mapiripán, El Retorno and northeastern Guaviare- with worrying situation.

Source: Ideam.

Secondly, the map included in the project design document shows, the reference area has dozens of roads, which is not the case in Matavén. Nor is it clear that such road development could be a foreseeable scenario in Matavén, given that the same document shows only one planned road: the one linking Villavicencio and Puerto Carreño, which would run through the grasslands of northern Vichada, far from the reservation.

This is important because roads facilitate logging, an expansion of the agricultural frontier and the appearance of settlements. The San José - El Retorno axis, in particular, has been a colonization front for decades, as research by biologists Dolors Armenteras and Nelly Rodríguez from Colombia’s National University shows.

.

WAYS. In bright green is the project area and in light green is the reference area.

Image: PDD de Matavén, taken from Renare.

Finally, the Redd+ project lies within an indigenous reservation, which holds a deed to the land and a factor that is usually associated with lower rates of deforestation, while the mirror area has a myriad of different owners ranging from private property and state-owned land to some indigenous reservations.

Research by Dolors Armenteras, published in the journal Biological Conservation in 2009, found that in the Guiana Shield -where Matavén is located- deforestation was 1.5 times higher along the outside border of indigenous reserves than within them. In other words, although this doesn’t stop deforestation, it does slow it down. This matters because -given that indigenous reservations are inalienable, imprescriptible and unseizable according to the Colombian Constitution- it is unlikely that land tenure will be rolled back in Matavén.

In short, the corridor used as a reference seems more exposed to deforestation risks, more easily accessible to external actors, and presents a different nature of land tenure.

ROUTES. Map of projected roads in Colombia. On the right, the future road to Puerto Carreño.

Image: PDD of Matavén, taken from Renare.

“Accessibility (legal roads and rivers) and tenure are key, and the two zones are different in actors, occupation patterns, development processes and accessibility. The more fragmented the forest, the greater the deforestation because the edge is exposed. And also, the greater the access, the easier it is to extract,” says a scientist who has studied deforestation dynamics for two decades.

These three factors led Carbon Market Watch to conclude that the second area is not a good comparison and that the project may therefore be presenting greater deforestation savings than it actually has produced. “This qualitative assessment of the baseline used by Matavén suggests that the baseline is inflated, because the reference area is not a realistic representation of what could happen in the project area if the project was not implemented,” its report says.

Asked about these three discepancies, managing company Mediamos defends its baseline: according to director Francisco Quiroga, it isn’t a question of designating equal areas but similar ones, and theirs meets the similarity criteria set by Verra’s VM0007 methodology. They chose it, he explains, after several geographic models and a deforestation trend forecast to which he attributes 95% reliability. “The norms establish how to choose the reference area, which has been backed by a methodology used by many projects worldwide and validated by auditors. If it did not comply, it wouldn’t have been accepted as similar,” he says, stressing that he has a master’s degree in statistics.

To these same questions, Verra also defended - in a questionnaire sent by its communication manager - that, in Matavén’s case, “the selection of the project reference area meets the requirements” and “reflects the greatest threats and deforestation factors for the project (cattle ranching, illicit crops, illegal mining and illegal timber extraction)”. It also stressed that it is logical that the second area has greater deforestation and a more extensive road network “given that it represents the situation of the project area and its surroundings in a counterfactual future in absence of the project.” Finally, it explained that “land tenure is not a criterion for selecting the reference region”, without answering if this reality does not create large differences between areas and even though it’s methodology does mention “legal rights to use land” as a factor.

“The baseline for each project is determined using the best scientific data and technological processes available at the time,” the certifier told this journalistic alliance. Verra also explained that it is adjusting its methodologies and that Matavén’s baseline will be updated “in the near future” following these new guidelines. In any case, these would not apply retroactively to how it counts tons of carbon.

Also asked about these three differences, the Environment Ministry admitted to this alliance - via a written questionnaire sent by its press team - that there may be discrepancies between methodologies and that, in its opinion, “it’s clear that an area with little road development cannot be compared to an area with high road development in terms of the risk of deforestation”, but that “the choice of a reference area is a methodological decision unique to the standard” and it’s up to the auditor -not the State- to verify that they comply with regulations. It omitted, however, that a 2018 regulation it passed allows it to request supplementary information, visit projects and even call for irregularities to be investigated. (For anyone interested, these are the complete answers from Verra and the Ministry).

In addition, Carbon Market Watch found that Matavén’s project presented a much higher projected deforestation rate than that of the Colombian Amazon: while the Colombian government officially calculated at 0.18% per year, Matavén chose one of 0.86% - or five times more, according to the European NGO’s numbers.

“It’s higher because it reflects the threat of deforestation on all edges of the Amazon and the Orinoquia, which has been moving from Meta and Guaviare, advancing towards Matavén,” says Francisco Quiroga, arguing that the rate set by the government covers the entire Amazon biome and doesn’t take into account that some regions are at greater risk than others.

In view of this discrepancy, the carbon market watchdog calculates that, under the official rate set by Colombia, Matavén should have issued some 6.86 million carbon credits, rather than the more than 25 million it has reported. That would mean that as many as 18 million credits could be illusory, but would have still been used to offset real emissions of harmful gases into the atmosphere.

.

An indigenous view on the carbon boom

Ethnic peoples are ideal partners for Redd+ projects because they can easily prove their ownership of large territories, thanks to the model of indigenous reservations and Afro-Colombian community councils that the Colombian state strongly promoted since the 1980s and to which the country’s 1991 Constitution granted special protection.

This explains why Redd+ projects have emerged in ethnic collective territories from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in the Caribbean and the Atrato River in Chocó, in northwestern Colombia, to the Amazonian trapezoid down south where Colombia meets Peru and Brazil, but also in peasant communities, such as in southern Huila.

In Matavén, indigenous leaders agree that the Redd+ project has brought them resources they never had before, which allowed them to unveil classrooms, 21 aqueducts, cocoa crops and even headquarters in Cumaribo and Inírida, although some raise concerns about its management.

“We don’t even know who the credits are sold to, nor how many or for how much. Very few persons really have an understanding of how this works and we are so far not educating the following generation so that hopefully one day they’ll be able to manage it autonomously, like the agreement with Mediamos stipulates” says Piapoco leader Pedro Eliseo Roa, who was Acatisema’s inspector and treasurer. In his view, greater transparency is needed, both in managing the project and in how its profits are invested. Despite this, Roa believes that “Acatisema is the mirror at a national level [of what a Redd+ project can be] and, in spite of everything, we’re passing the test”.

A second indigenous leader agreed with this vision, but preferred not to discuss the issue until they finish the process of reforming the reservation’s internal rules. Although these revolve more around issues of self-government, it’s likely that these proposals -which they have been preparing for a month and will socialize with all communities in July prior to their approval - will allow them to rethink the way in which some aspects of the project have been working.

Opiac, which brings together the indigenous peoples of the Colombian Amazon, defends the importance of Redd+ and other payment for environmental services schemes, such as habitat banks and biodiversity credits, but insist on the need to strengthen communities’ skills to lead them and reduce the control many intermediaries have over projects.

“We want them to be clear, transparent and participatory businesses, where the direct benefit is for the indigenous communities,” says Mateo Estrada, a Siriano indigenous leader and Opiac’s climate change expert. In fact, the organization is currently working on a model contract that can be used by Amazonian communities as a guide.

The indigenous people feel that the State has been absent in regulating a new activity where there is still a huge knowledge gap between actors and where companies without environmental track record have proliferated. “It’s the government’s responsibility to train indigenous authorities in their territories: not with basic workshops on what the carbon market is, but with complete courses detailing all the current legislation, how standards work, what the social and environmental safeguards that projects must comply with are and how to negotiate as equals,” says Estrada. “The state is failing to accompany us,” adds Roa.

The boom has led many indigenous leaders and environmental scientists to fear that unscrupulous persons might persuade communities to grant them the right to trade carbon credits on their territories under unfavorable conditions for them.

One case cited by four persons is that of the Nukak Maku reservation in Guaviare, whose 954.000 hectares of jungle -adjacent to a similarly named national park- are home to some 1.080 Nukak Indians, a nomadic ethnic group that remained in voluntary isolation until the late 1980s, which does not have a robust organizational structure and is considered among those at greatest risk of physical and cultural extinction in Colombia. In particular, they are concerned that contracts may include terms such as 100-year irrevocable commitments, which is what Waldrättung SAS proposed to the Nukak, as stated in a document obtained by this journalistic alliance.

.

ALERTS. One hundred year time limits, as in this document with the Nukak Indians shows, are one of the contract clauses that concern environmental scientists and indigenous organizations.

Capture: Nukak indigenous.

“I’ve heard of proposals to communities where, for example, 50 percent of the income would go to the partners for the mere fact of setting up and managing the project, while the indigenous people did the actual conservation effort and provided the land. Or others that would stand for 50 years without review, even though you can’t know what the market conditions will be in the future. It is very difficult to obtain consent on those terms”, says a public official who has worked with indigenous communities for two decades. Although that is not the case of Matavén, it shows some of the complex situations that have arisen and that also require the Colombian government’s attention.

The government argues that it’s not responsible for monitoring relations between companies and communities. The Ministry of Environment responded to this alliance that “it does not carry out any supervision of the resources generated by the Redd+ Matavén project, given that this is a private initiative and, therefore, it is governed by the jurisprudence that assists it as an entity that exercises a commercial activity under private law”.

Mediamos’s Francisco Quiroga, who underscores that they arrived in Matavén on invitation by Acatisema, also admits that it hasn’t been an easy process. In addition to skepticism from part of the community, barriers such as banks’ refusal to lend money for these projects and even having had to sell a building in Cali to fund it, he believes that the Redd+ model is the best possible for Matavén because, in his words, it’s the only one allowing, at the same time, “to reduce deforestation, conserve the rainforest, preserve the communities and seek their wellbeing.”

Asked how much money this project brings to the company he leads, he doesn’t answer directly. He explains that 10% of the income from credit sales is destined to administrative costs, paid to the intermediary companies, while another 10% corresponds to Mediamos. The remaining 80%, he explains, goes to the community and is invested in projects decided jointly by them and Acatisema.

A hole in Colombia's pocket

Since January 1, 2017, Colombia has had a carbon tax seeking to penalize the use of fossil fuels, thus fulfilling the country’s commitments under the Paris Agreement negotiated one year before.

This means that individuals and companies must pay the state a 17.660 peso surcharge (about 4.7 dollars) for each ton of carbon dioxide emitted, as compensation for this environmental footprint. That money is then used for programs mitigating climate change or counteracting its negative effects, including preserving water sources, slowing coastal erosion or restoring ecosystems.

It was the same tax reform by then-President Juan Manuel Santos that created the new green tax in 2016 that allowed companies that proved they offset their carbon emissions with bonds or other green investments to opt out. The task of regulating this exemption fell upon the Environment and Finance ministries, which in a June 2017 decree established the conditions for companies to prove they own carbon credits equivalent to the emissions generated by their fossil fuel consumption and request not to pay the tax. For many companies, this option -dubbed ‘non-causation’- became attractive given that credits are cheaper than the tax.

Due to the complex architecture of the tax, it is collected at the time of purchase of various taxed fossil fuels, including gasoline, kerosene, jet fuel used by planes, diesel fuel, fuel oil and, in some industries, natural gas and liquefied petroleum gas. Those who buy carbon credits then present them to distributors -such as Ecopetrol, Terpel or Primax- and ask them to subtract the tax.

The effect of a company paying with a hot air credits -even if has purchased them in good faith- is that the Colombian state sees a drop in its tax collection.

As a person working in the environmental sector says, “if a company like Latam or Cabify tells you as a user that its operation carbon neutral, you want to believe that the gases emitted by those planes or cabs are being offset by carbon capture in forests or in places that are no longer being cleared down”.

If we are talking about millions of credits, as in the case of Matavén, the drop in revenue can end up being equally in the millions. “This is equivalent to a loss of revenues of US$ 18.9 million for the Colombian government, attributable to the use of hot air credits,” Carbon Market Watch calculated.

Although the carbon tax is specifically earmarked for the environmental sector, in a crisis like the current one, this money could fund productive solutions that are also green.

It could, for example, be used in the reconstruction of Providencia after Hurricane Iota, executing the ignored recommendations of the Caribbean island’s climate change adaptation plan, such as restoring coral reefs and mangroves that help cushion the blow of severe storms. Or to finance social projects with an environmental vocation, such as the ‘forest warden families’ of the Uribe administration, the ‘peace forests’ of the Santos administration or the 180 million tree-planting pledge by the current Duque administration.

In times of fiscal stringency due to the pandemic, that money that stopped arriving to the Colombian State’s coffers -and whose execution has been very slow- is even more lacking – especially if this is happening not only with one project but with more of them.

The blow -also economic- to the Amazon's flagship program

There is an additional problem: as a result of potentially inflated bonds, Colombia is not only failing to collect money from the carbon tax, but potentially also receiving fewer resources from international cooperation in its flagship project to curb deforestation in the Amazon.

The reason is that there are two types of Redd+ projects. On the one hand, there are the individual ones, such as Matavén, which constitute the voluntary carbon market. On the other hand, there are regional state-sponsored initiatives, such as the one already created by the Colombian government for the entire Amazon biome, which operate under a similar logic, but with a much broader geographic focus.

Through the latter program, dubbed Vision Amazonia, the governments of Norway, Germany and Great Britain finance projects that support a different -and greener- development model for this region. They do so through solutions ranging from strengthening local communities’ governance to promoting sustainable economies such as community-based tourism or biotrade of forest products such as asaí, copoazú or cacao. In the end, they do not buy credits, but ‘pay’ Colombia for its results in reducing deforestation.

Vision Amazonia established a deforestation rate for the entire Amazon biome of 82,883 hectares per year, which it calculated using the historical average from 2000 to 2012 and which the Colombian government officially submitted to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. It added an additional 10% in anticipation of greater forest loss for at least five years, on account of governance voids in areas that used to be under the control of the former FARC guerrillas up until the landmark November 2016 peace deal.

The resources that the three European countries transfer to Colombia are calculated, year by year, by looking at how much the country managed to reduce deforestation in the Amazon. In other words, the payment is not based on credits, but on results on the ground.

But for this result to be true to reality, the Colombian government must subtract from this figure any other deforestation reductions that have been paid to other actors in the region. For example, a commercial timber plantation cannot, at the same time, sell wood and carbon credits for those same trees. The logic is that two different people cannot be paid twice for the same positive feat. In other words, no double counting is allowed.

In August 2018 the Ministry of Environment unveiled a resolution to deal with some of these issues, explaining how different activities seeking to mitigate emissions must monitor, report and verify their results and avoid such double counting.

That 34-page resolution, unveiled just six days before the end of the Santos administration, also laid down how individual projects like Matavén should fit -or be ‘nested’, in climate jargon- within the wider program for the entire Colombian Amazon.

In broad terms, it outlined two possible paths. Projects after the decision must set a methodology that is in line with the government's deforestation reference level. For those created before, even if they already have a baseline, the government must assign a ‘maximum mitigation potential’ that determines the maximum number of credits they can issue. In other words, in both cases, in the end they have to nest within the official deforestation calculations.

In Matavén’s case, this means that the project should follow the deforestation rate set by the government and officially communicated to the UN: for the period from 2016 to 2017 it should follow the ‘forest reference emission level’ for the Amazon biome, only allowing those credits within those numbers to be deemed worthy substitutes for the carbon tax. Then, beginning in 2018, it should adjust to the national deforestation rate that the Colombian government submitted to the UN a year and a half ago, and still pending approval.

However, according to its auditors’ reports, Matavén has not yet adjusted its deforestation rate to the official ones and thus it has been possible for buying companies to use the project’s 2016 and 2017 credits to prove the neutrality of their carbon emissions, a fact that seems to have been overlooked by the certifier Verra, verifiers, traders, buyers and even the Ministry. Something similar could happen with the 2018 and 2019 credits already verified by Epic Sustainability, if Verra now issues them without them being adjusted to the new national rate that is already in effect.

These inconsistencies have already had an effect on the Colombian government’s funding for the Amazon.

Given that Matavén lies within the Amazon biome, European donors asked Colombia to check that they were not paying twice for the same tons avoided. “The governments of Germany, Norway and the United Kingdom (...) have been emphatic that there should be no double counting for the reductions generated by the Matavén project,” the Ministry of Environment confirmed to this alliance, adding that for the period between 2013 and 2017 it subtracted those figures from those of Vision Amazonia. In a document submitted to the Green Climate Fund, the government quantified that cost in 3.5 million credits.

Francisco Quiroga of Mediamos acknowledges that there is a divergence in the way the government and they understand the norm, but -in his opinion- it could be solved with solutions for those actors in the market before the Environment Ministry began to regulate it.

“We understand that there should be a nesting and that it should happen on the basis of the national reference level, but we also believe that there should be a transition regime so that the baseline that we had already established, that a certifier approved according to its standard and that the Ministry knew about, is respected,” he says. In his view, the regulation harmed them because it disrupted their budgets and the investment plans made with Matavén’s communities, which include cocoa, agroforestry projects with mahogany wood and nature tourism.

Mediamos defends two specific proposals. First, that they be allowed to maintain their baseline until the end of its ten-year validity in 2022 because, in Quiroga’s words, “it cannot be made retroactive”. And, second, that in the future Redd+ projects that overlap with Visión Amazonia are not assigned equal quotas, but rather, he says, use “an allocation instrument that takes into account each project’s deforestation risk, because threats are not the same”. Under this criterion, they ask that Matavén be considered as facing a higher risk because it lies in the transition towards the rest of the country and not, for example, in the heart of Vaupés. This is an idea, he says, which Asocarbono, the industry association grouping carbon credit companies that Quiroga himself co-founded, agrees with.

“It took the government too long to regulate and those delays usually create spaces for interpretation. It’s those gaps that have allowed problems to appear,” says a person who has worked in the Amazon for two decades.

.

A system with problems

The questions raised by Matavén go beyond its borders and point to a broader problem.

It isn’t the only Redd+ project in the Colombian Amazon where Carbon Market Watch found inconsistencies: its analysis points to similar problems in the Kaliawiri project, also located on the border between Vichada and Guainía. As with Matavén, CMW notes that the initiative -developed by the consulting firm BioFix and certified by the Colombian ProClima standard- differs significantly from its reference area. Their conclusion is that the baseline may also be inflated, leading to potentially 2 million carbon credits more than if it had nested within the official Amazon rate, as regulation demands, and possibly US $10 million in forgone tax revenue.

Ultimately, Matavén could be a microcosm of the system’s shortcomings. Although the projects gain from the deforestation they manage to avoid, it is not easy to ascertain whether the area they chose as a mirror is really equivalent and excessively fatalistic scenarios -which don’t match reality- inflate their figures.

“It is a system-wide failure of the market which allowed this to happen, given that project developers, the Ministry, the independent verifiers, and the standard did not raise any concerns regarding this potential over-issuance,” Carbon Market Watch concluded.

The incentive seems to be to place the maximum volume of credits on the market, a situation in which all actors in the chain benefit economically. In this win-win situation, many lose their capacity to serve as checks and balances: neither the standards that stamp their seal of approval, nor the independent verifiers that must audit a project’s performance, nor the traders that guarantee the quality of the credits sold seem to be looking into these incongruences. In practice, they end up being judge and judged, which contributes to the fact that many end clients -confident in the due diligence of others- are possibly not aware of how legitimate the credits they bought are. As a former public official says, “the role of intermediaries has eaten the market”.

There is also a lack of technical knowhow in the Colombian government to deal with the market’s filigree and oversee that projects function properly. The Environment Ministry does not have a team to follow up on each project. Likewise, the DIAN, the national tax agency, has no way of verifying that those requesting exemption from the carbon tax are in fact buying legitimate credits.

In addition, it is very difficult for civil society to monitor how and where these credits move.

Renare, the government platform listing mitigation projects promised in 2018, announced in 2019 and only operational since late 2020, is difficult to navigate. It is not easy to consult neither the maps nor the number of credits issued nor their buyers and, in many cases, not even the project design documents that are their basis.

All sources consulted agree that Colombia has made progress in consolidating a market needed to reduce deforestation and that it has been a pioneer in this, but they suggest steps to correct some of the problems that have become evident.

“As the market has been poorly regulated and Renare is just beginning, there have been no clear ground rules and that has generated many problems. There is also no traceability or easy access to information, which has been one of the international aid’s conditions,” says a forestry policy specialist. In this person’s view, Renare needs to be fully operational, the skillsets of different government agencies have to be strengthened and the Environment Ministry needs to have more clarity on which areas are already committed to programs like Vision Amazonia so companies and communities are fully aware.

“Our institutional weakness hinders us from deploying the full potential of the carbon market in Colombia with participation from private capital,” argues Francisco Quiroga, who insists that the country would benefit more economically with projects like his than with European donors. “Who prevents logging, illegal mining, deforestation or coca cultivation, if not the communities themselves? In our project they’re a human wall against these risks. If our project were not there, what is happening in the reference region would do so in Matavén”.

“Agreements should focus on improving the quality of life of communities. The government should play a more active role in ensuring that this is the case,” says the lawyer who has advised indigenous communities.

Colombia is not the only country where methodological critiques have rained down on the Redd+ model. A joint investigation by the Guardian and Greenpeace’s journalistic arm Unearthed last month examined 10 Verra projects chosen by airlines and concluded that “although projects often provide benefits to the environment and local communities, attempts to quantify, commodify and market the resulting carbon savings as a ‘carbon offset’ are based on shaky foundations”. Another story by MIT Technology Review in April reaches a similar conclusion regarding California’s government-led program, which is based on rewarding areas more thickly forested than the average rather than comparing with reference areas.

“We cannot count pears in the Amazon, apples in Chocó and oranges in the Orinoquia. We need a minimum of equivalence, to have measurable and accountable results, and to be sure that we are indeed curbing emissions. A win-win situation for everyone involved is good news if the reductions are real”, says another person from the sector, for whom the urgent need to continue regulating is not exclusive to the carbon market, but rather something in common with most climate-related issues, still in their legal infancy.

Asked how different sectors of Colombian society can trust that all carbon credits resulting from Redd+ projects actually represent avoided carbon emissions, Verra responded that “projects certified under the VCS Program undergo rigorous, credible and transparent evaluation processes that are verified by independent auditors”. It also stressed that its standard has been approved by various national governments and by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), although when pressed further it acknowledged that its VM0007 methodology -and therefore Mataven- doesn’t currently produce emissons reductions considered eligible by the UN's aviation agency.

However, many environmental scientists in Colombia and abroad remain concerned that some of these projects might be creating paper reductions that promise mitigations that never happened and affect the credibility of projects that are doing things right (but are likely to have a harder time producing real reductions) and deal a blow to the public wallet. And that by buying such credits, companies such as airlines or transporters avoid paying the carbon tax, while the core problem -their greenhouse gas emissions- remain in the same levels and heading towards the atmosphere.

“The country is working on a more robust regulatory framework that seeks to cover issues and fields of action where there are still gaps not covered by Resolution 1447. Closing them will be an important step in ensuring that REDD+ projects demonstrate credible mitigation results consistent with our national accounting,” the Ministry told us in a questionnaire sent by its press team. It added that it’s currently working on a four-pronged strategy to strengthen the market, including improving regulatory framework, human skills, operation and government oversight.

In a context of economic crisis and a marked need to find new sources of revenue, the Duque government -which, for instance, has successfully ramped up solar energy projects to speed up the energy transition- could evaluate whether setting up a robust monitoring system and a technical team to lead it costs less than continuing to unnecessarily lose green tax revenues.

In the long run, such double counting could become a reputational problem for Colombia, which is trying to convince the world that it is serious about reducing net deforestation in the Amazon to zero and has focused part of its diplomacy on persuading other countries -especially in Europe- to put up the money to do so.

Brazil, home to the largest portion of the Amazon, has already experienced the consequences of not living up to its promises. In 2019, Norway and Germany suspended their contributions after President Jair Bolsonaro changed the management rules for his Amazon fund, which his donors interpreted as a sign that the country isn’t taking appropriate measures against deforestation that has run amok during his term. Norway alone had contributed $1.2 billion to Brazil in a decade.

Both Vision Amazonia and Redd+ projects are critical for Colombia because they bring resources that Amazonian communities desperately need, given that they play a crucial role in protecting the rainforest, but there are questions about the traceability and transparency of the latter.

“That such incentives reach the territories is very good: that is a paradigm shift -says a person who works in the sector- But what is at stake today is the efficiency of the distribution of those funds and the credibility of the counting rules. If it’s not credible, the market will only be a fleeting bloom.”

The ultimate aim of the Redd+ mechanism is that fewer polluting gases are released into the atmosphere, so -if in real life those emissions are not falling- the result is a false sense of progress. According to people working in the sector, that should be the yardstick: if it doesn’t reduce emissions, it doesn’t work.

“It's not that the market is perverse, but that there is a need for greater controls, safeguards and proper oversight,” says another person working in climate finance. “We end up with a paper fair and with no real emission reductions. We’re simply patting ourselves on the back.”

Following the publication of this story, Primax Colombia contacted us to explain how it evaluates the carbon credits it purchases and to clarify that it only purchased Matavén credits in 2019. We added their perspective because it helps to better understand the issue.

Primax explained that it requires that credits meet all current norms and are validated by verifying companies, as required by law. For this reason, it concludes, "Primax fully and strictly complies with all the requirements established by the current regulations for the non-causation of carbon tax, which (...) implies the observance of due diligence". In response to the question of how they guarantee that these credits in fact come from natural areas that are reducing their deforestation by virtue of the project that issues them, the company emphasized that it's the verifying companies that must ensure that this is so. "They are the entities that must guarantee that the projects comply with the environmental purpose for which they were created," it stated. Ultimately, although it does not use those words, Primax argues that it is a good faith buyer that trusts that the other actors in the chain have done their job properly. (You can read Primax's full response here).

BioFix also contacted us to express its objections to the conclusions of the Carbon Market Watch report on its Kaliawiri project. For BioFix, the company that structured this project, the report uses false and subjective arguments to claim that its baseline is inflated, errs in that it did not require requesting a maximum mitigation potential, and ignores its benefits for the indigenous communities in the area. In addition, BioFix reiterates that its methodology follows Colombian regulations and points out that they and other companies have been working from Asocarbono with the Ministry of Environment "to clarify the application of Resolution 1447". "The impact achieved by these projects in social and environmental matters is significant," it concludes.

In its public statement BioFix does not explain, however, whether its Kaliawiri project - given that it was validated after that resolution came out - should directly adjust its projected deforestation baseline to the official reference level for the Amazon biome and whether that would apply to avoided emissions in the 2013-7 period (within which Kaliawiri verified credits for 2016 and 2017), which was Carbon Market Watch's main critique to its project. We asked them this question and at the date of updating the story we were awaiting their response.

Tienes reportajes guardados

Tienes reportajes guardados