His life for a tree. William Angulo was still cutting the trunk of the cedar tree when he was struck by nine spears. Although he survived the initial attack, he died days later of an infection at a public hospital in Quito, some 320 kilometers from the site in the Amazon where a group of indigenous people in voluntary isolation had set upon him.

His partner, Andres Moreira, had better luck and survived to tell the story. Together, they had travelled to the isolated site in the Ecuadorian jungle to extract timber.

Seventeen loggers from various population centers had gathered at the location. Over a period of 18 days they had worked around Cononaco Chico—about 90 kilometers from Coca—feeling cedar trees. They had been hired by a patrón (a boss) and hoped to earn a daily wage of US$10. The work is informal and is not covered by life or accident insurance.

Photo: Fundación Labaka – Milagros Aguirre

The cedar was extracted from a protected area of the Yasuní National Park. Four trucks were used each week for transport. In her book ¡A quién le importan esas vidas! (Lives don’t matter), journalist Milagros Aguirre Andrade uncovered this timber trafficking in one of the world’s most biodiverse natural areas. Eleven years after her first reports, she assesses the current situation: "…although they have installed an official checkpoint, in all this time they have been unable to catch a single logger in Coca..."

Since first contracted by American missionaries in the middle of the last century, members of the Waorani indigenous community have been participating in the logging cycle, whilst others, distant relatives, formed clans that chose to live in isolation and avoid any form of contact. It was people from this latter group who attacked Andrés Moreira and the other loggers.

Isolated and cornered

“Some of the Waorani who once participated in logging later changed their activity and went to work for oil companies,” says Milagros Aguirre. However, trafficking continues in the area. During inspections of the southeastern part of Yasuní National Park, the country’s ministries of environment and justice have found camps used by operators who use the Napo River (one of the Amazon’s main tributaries), to send illegally extracted species to Peru.

Photo: Agencia Tegantai

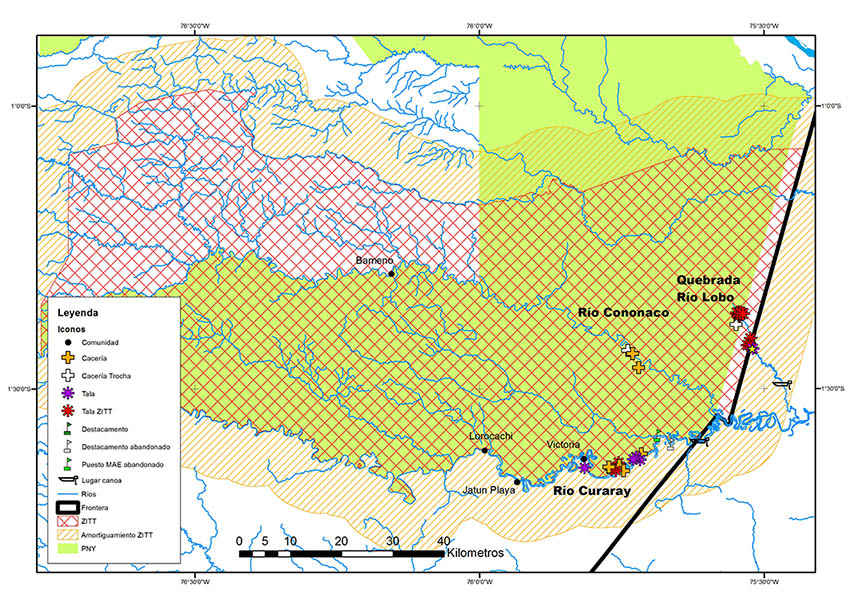

The Tagaeri Taromenani (ZITT) protected area covers more than 750 thousand hectares within the Yasuní National Park. Occupied by indigenous people living in isolation, it is an zone in which the exploitation of natural resources is banned.

“[Due to the entry of illegal loggers] the situation for these isolated people is delicate” says Washington Huilca, a researcher who has led expeditions into the area as part of a joint effort of the Alejandro Labaka Foundation, Acción Ecológica and Land is Life, all non-governmental organizations working in the Amazon region. “What concerns us most is that they are cutting down cedar,” says Huilca.

Photo: Edú León

According to a technical report prepared by the one of the expeditions, groups of loggers—some believed to come from Peru—enter the protected areas to hunt animals and cut down chuncho and cedar trees. This latter species, known also as red gold, can be traded at US$3000 per square meter. According to David Suárez, an expedition member, "the absence of state controls means that timber can be illegally traded on the Peruvian border."

Between the ilegal and the informal

Although logging in the southeast margin of Yasuní Park can be regarded as an illegal activity, Elena Mejía, a researcher at the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), explains that in other areas it forms part of self-sustainability projects.

In 2013 Mejía was a member of a team of experts that gathered information about the timber markets in Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia. These markets in Ecuador are concentrated in the provinces of Orellana and Napo. The team found that the majority of farmers (indigenous Kichwa, Shuar and settlers) exploiting their forests did so on a small scale as part of projects with the Ministry of Environment which aimed to make the activity sustainable.

“Logging is risky and expensive. A person who has several hectares (a farmer) relies entirely on family labor. If a tree falls on someone, there is nobody to help. Several communities in Ecuador undertake this activity out of necessity,” says Mejía.

Photo: Edú León

The study in Ecuador also revealed that small-scale loggers—the bottom link in the marketing chain—are the ones who receive the least income. The highest economic returns go to the middle men and the companies. Part of the timber that leaves the Amazon is used for construction, ends up in sawmills, or goes to factories that manufacture furniture. A significant amount is also sent to Huaquillas, on the border, and later to Peru.

The official data which we accessed for this investigation indicates that Ecuador extracts between 3.5 and 3.9 million cubic meters of timber each year, 80% of which comes from pine, eucalyptus, teak and balsa plantations located in coastal regions and the highlands. The remaining 20% is extracted from native forests located mainly in the Amazon through a sustainable development project led by the Ministry of Environment. Some 40% of the overall total is exported.

In 2017, Ecuador exported sawn timber (mainly balsa and teak) valued at approximately US$91 million and processed products such as planks (pine and eucalyptus) valued at more than US$120 million.

Photo: Fundación Labaka

Ecuador’s leading export companies also own the entire production chain, from the plantations, through to the harvesting, processing, and distribution. The list of companies includes Plantabal, Novopan, Diab Ecuador, and Cobalsa..

Colombia is the primary destination for Ecuador's timber exports and receives the largest number of plywood sheets. The United States is the second most important market. The main destinations for sawn wood are China and India.

Closed season for mahogany

Last October, a 10-year ban on mahogany or ahuano (Swietenia macrophylla) came into force. Since 2013, it has been listed in Appendix II of the agreement of the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). According to the Ministry of Environment, the provinces of Pastaza and Morona are home to Ecuador’s last remaining populations of this species.

Photo: Agencia Tegantai

How will the environmental authority enforce compliance with the ban? According to the authority, it will increase checks along the roads, undertake mobile surveillance on particular routes, review forest management programs, and conduct audits to trace of product to its final destination (industries, sawmills, storage centers, among others).

The control team has 82 technicians throughout the country, located in 41 forest offices. At the same time, the National Forest Control System project has 68 specialists located in the provinces where the possibility of conflict is greatest. “The officers are trained to recognize the species that are harvested and traded,” explains the authority.

However, forestry expert Walter Palacios warns that the decision to ban extraction for ten years will only be positive “to the extent that complementary measures are taken, including a general inventory to assess the state of the population, and effective control of illegal logging.”

Penti Baiwa, an indigenous Waorani who lives in Baameno, one of the three communities settled in the protected area of the Yasuní National Park, remembers his father, “He was a warrior who defended the jungle with spears. And we are also going to defend it from the coworis (loggers) who want to take timber.” The timber is illegally extracted from the Ecuadorian Amazon and is then incorporated into the formal chain of trade and industry.

Tienes reportajes guardados

Tienes reportajes guardados