When he returned home to Manaus from a trip to Rio de Janeiro in April 2020, anthropologist and indigenous artist Jaime Diakara felt the first symptoms of Covid-19. He had a fever, body ache and headache. From what he saw on television, he deduced that he had been infected with the new disease. With no clinical tests and collapsed hospitals, he and his entire family, who were also infected, isolated themselves in their home and decided to treat themselves there. "We used various herbal teas and blessings," he says.

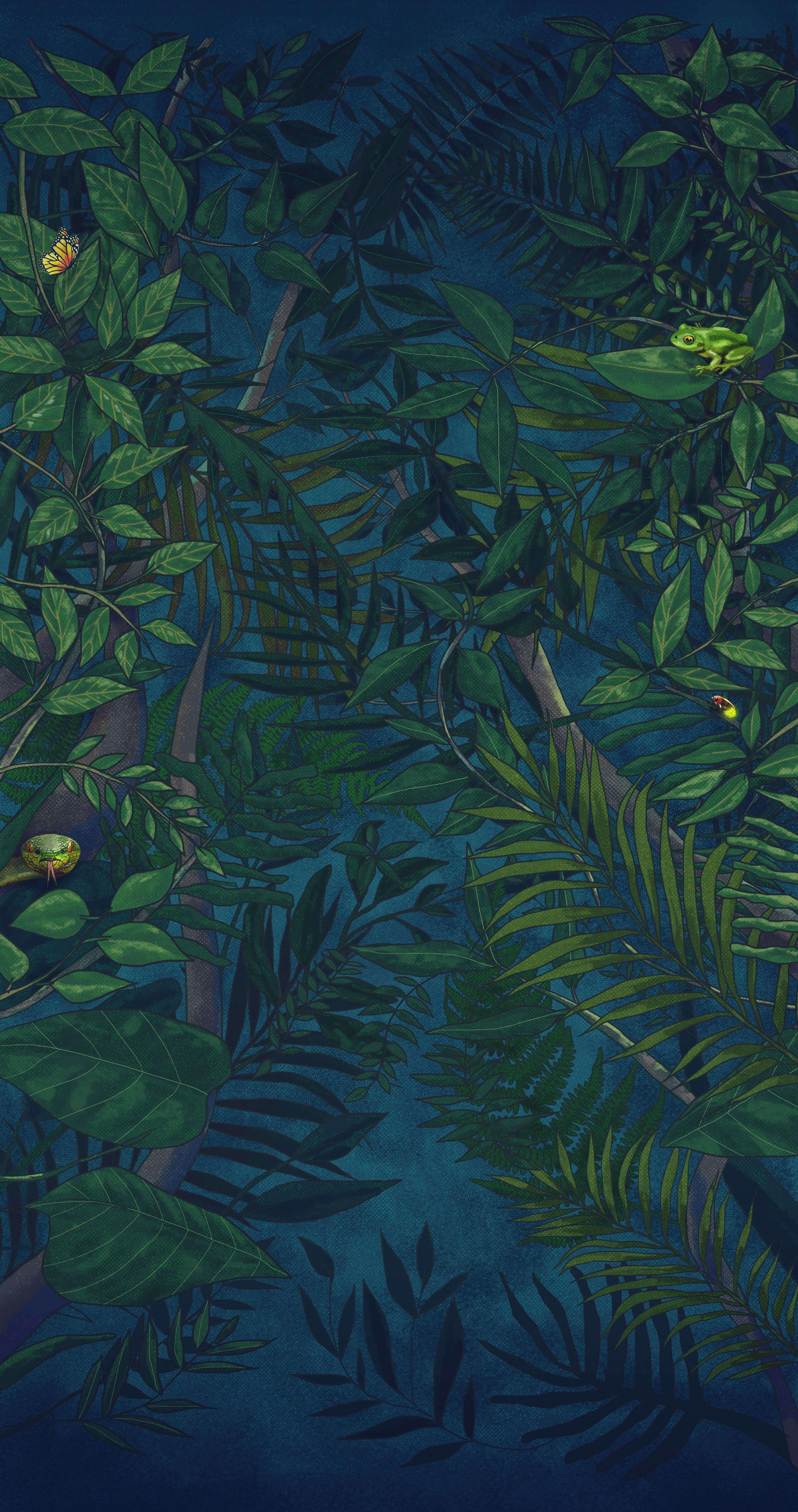

Aware that he was living an important moment, Jaime decided to use the language of art to record what was happening. "I started sketching on paper everything I was feeling and that's how I made this drawing," he recalls, showing one of the first paintings he made during the pandemic. It was the expression of physical discomfort combined with uncertainty.

CREATIVE PROCESS. The drawings made by Jaime Diákara represent the symptoms of Covid-19 in his body. Photo: Izabel Santos / OjoPúblico / Infoamazonía

CREATIVE PROCESS. The drawings made by Jaime Diákara represent the symptoms of Covid-19 in his body. Photo: Izabel Santos / OjoPúblico / Infoamazonía As the new coronavirus progressed in Jaime's body and weakened his health, he continued to paint, to draw. "From tht point, I created drawings and graphisms. I turned that work into my treatment and called that production 'healing art.' It was as if I were taking the disease out of the body with art," he explains.

The indigenous people to which Jaime belongs, the Desana, are one of the groups of the Eastern Tukano family that inhabit the border region between Brazil and Colombia, in the municipality of São Gabriel da Cachoeira, located in the Brazilian state of Amazonas. However, Jaime, like many from other indigenous peoples, moved to Manaus, the state capital, more than 10 years ago to study. He is part of the 36% of Brazil's 896,000 indigenous people living in urban areas, according to the official 2010 census.

Jaime Diakara is also one of the researchers of the Centro de Antropología Indígena de la Universidad Federal de Amazonas. And, precisely since the beginning of the pandemic, they have been collecting texts, audios, and artistic manifestations of the diverse impacts caused by Covid-19 on the indigenous peoples of Amazonas.

Manaus was one of the cities most affected by infections and deaths. In April 2020, the health system collapsed and images of people dying, for lack of oxygen or of an intensive care bed, at the doors of hospitals and in their homes traveled the world.

"The pandemic changed, even, our way of thinking has changed, and this is going to change the way we live," says Diakara.

"The arrival of the pandemic had a great impact on the life of the indigenous people. In the city and in the communities, we stopped going out and practicing our collective rituals, which was one of the worst things the disease brought us. Indigenous people everywhere need to move from one place to another to work and buy food. And many of us are self-employed, selling handicrafts, performing dance rituals, or are engaged in commerce in the city. With social isolation, we are very constrained," says Jaime.

With limited access to health services, many indigenous people residing in the city who became infected turned to their ancestral knowledge and began treating themselves at home. "I cured myself using bahsese [a ritual similar to a blessing] and using leaves and stinging-flavored fruits," Jaime recalls.

"We apply bahsese to the liquid from these plants, calling the virus by name to kill it, and we do our protection and our healing.” In the Desana tradition, there are three important elements for protection against a disease: the breu (resin extracted from a tree), the cigarette and the liquid (infusion of leaves). "That's our way of dealing with the disease and that's how we are reinventing ourselves to survive while the vaccine reaches everyone," says the artist.

In Brazil, indigenous people are part of the priority groups to receive the vaccine, which began to reach their arms in January this year. But at the beginning, the Ministry of Health excluded from the groups those who, like Jaime, do not live in indigenous lands. After a long wait, a few weeks ago, the indigenous artist was able to get vaccinated.

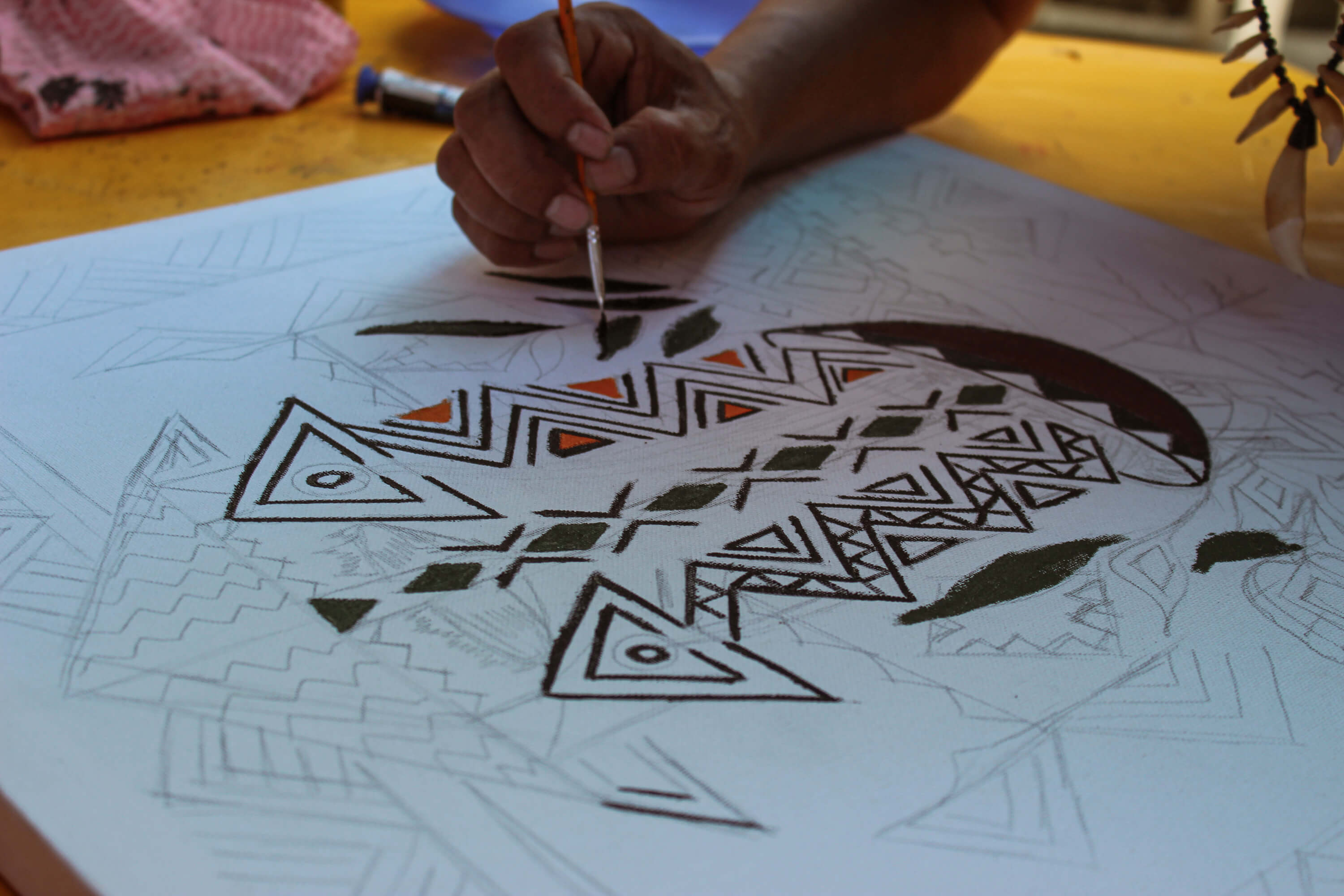

How did the pandemic impact the indigenous world view? The work that Jaime Diakara created for this journalistic series “Visiones del Coronavirus” (Visions of Coronavirus) represents the impact of the pandemic on his people. The result is the canvas "Wanani Goãmū" or "The Master of the Medicinal Plants" in Wanni, the language spoken by his people.

The image by the artist represents the confrontation of the body against the new coronavirus through the opposition between light and shadow —rising and setting sun— supported by the "pumpkin of the world," which sustains the universe according to Desana cosmology. "The invisible beings that cause Covid-19 attack us from the side where there is no light, the left side. That's why we use protective graphisms on this part of the body," explains Jaime.

ONGOING STRUGGLE. Jaime Diakara's canvas "Wanani Goãmū" depicts the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on his village. Photos: Izabel Santos/ OjoPúblico /InfoAmazonia)

ONGOING STRUGGLE. Jaime Diakara's canvas "Wanani Goãmū" depicts the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on his village. Photos: Izabel Santos/ OjoPúblico /InfoAmazonia)Jaime Diakara is 41 years old and spent his childhood and adolescence listening to stories about the rituals of his Cucura Igarapé community. He moved to the city to study and now holds a PhD in Anthropology from Universidad Federal de Amazonas.

The artist says that the greatest threat to the existence of Brazil's indigenous peoples is not disease, but the lack of public policies and actions for their well-being. "Indigenous people living in the interior of the state have to leave their communities and go to the headquarters of their municipalities for help, food, assistance, everything, because those who used to bring it there have stopped doing so. The communities, the indigenous villages and everything else have been locked in isolation. But hunger and need do not respect social isolation, they enter our lives, our communities, without asking for permission," he says.

The pandemic has affected not only indigenous people living in their communities, but also those living in the city. "It changed my way of living. It has totally changed the way we relate to each other. Now we can no longer sit down, talk and discuss our needs. I would even say that it has changed our way of thinking and this will renew our way of practicing life," Jaime explains.

Brazil's official figures show that as of July 2020, more than 547,000 people have died from Covid-19. Of this group, more than 34,000 lived in indigenous territories, according to information from the Pan-Amazonian Ecclesial Network. During the months of the health emergency, the violation of human rights against indigenous peoples in this country has worsened.