Planes. Many, flying like huge birds in the sky. This was Wilder Allui’s dream before the coronavirus invaded his community. It reminded him, an awajun 26-year-old painter, of a sci-fi movie where the good guys fight the bad ones. In his dream, the forest trees became planes and face the evil aircraft that pretended to destroy his habitat. The bullets remained suspended in the air, and the combat turned intense in the sky, until the invaders were beaten and fled. Below, in the earth, Allui and the rest of inhabitants celebrated their triumph.

That day, when he woke up, the youngster asked his father for the meaning of that dream. The wiseman of the Soritor community, located in the Peruvian north-oriental region of San Martin, in the Ecuadorian frontier, answered decidedly: “There will be trouble, a disease is coming.” Some days before, Allui had heard that in another community somebody had dreamt of a burning fire that devastated the houses and the forest trees. People panicked and dived into the river, but the fire chased them even to the water. Some were saved and could go back to their community, but many died.

Allui asked his father about that dream he had heard of, and the answer of his father was similar: “ A disease is falling, there will be death.” Since then, Allui and the Soritor indigenous people knew a plague was coming, but they ignored when and what it would look like. They called it ‘yamajam jata wainchatai iyaje’, that means “a new unknown disease has arrived”, in the Awajun language. However, at the beginning [in March 2020, when the disease started to expand in the cities] they felt protected by the huge distances between them and the apach (mixed race people).

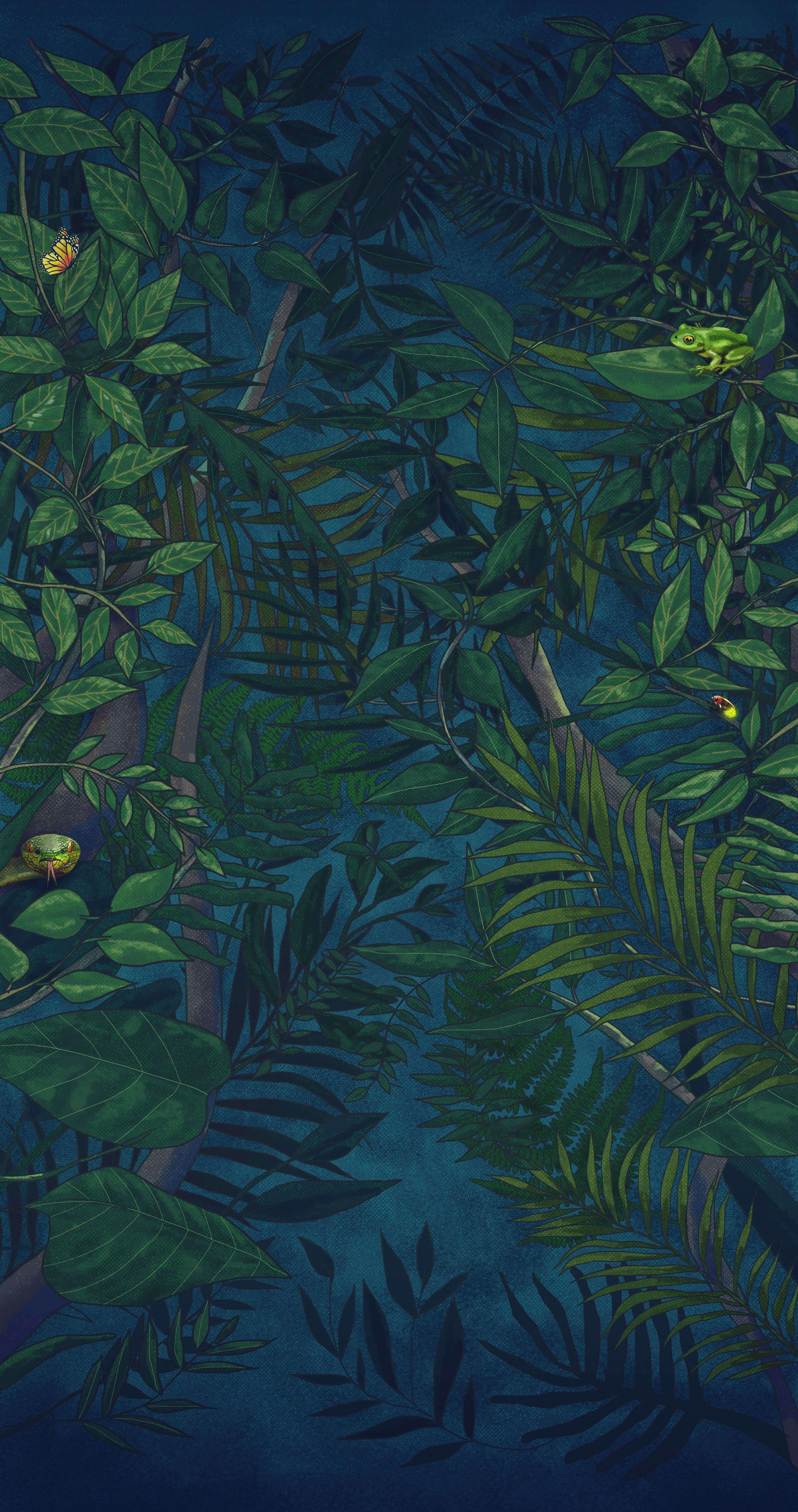

FIGHT AGAINST DEATH. The artist Wilder Allui depicts the importance of knowledge and the connection with plants in the face of the threat of death brought.

FIGHT AGAINST DEATH. The artist Wilder Allui depicts the importance of knowledge and the connection with plants in the face of the threat of death brought.Allui’s relatives had heard that Covid-19 was something like the flu, with chest pain, but people did not die. That is what they told Wilder. Therefore, feeling safe, he played friendly football matches in the community and gathered to drink masato, a beverage made of yuca. Nobody was ill. However, as months passed, in June of last year, news arrived from the Marañon River basin: people started to get ill and die. The virus installed in Soritor and “we started to fall”, says Allui. Scared, people lock themselves inside their houses to be saved.

Now, more than a year since that sci-fi movie came true, Allui says that he has understood his dream; the planes that fought for them were the forest plants. “The plants fought against the disease”, he points out. But that combat was not easy. On the way, they carried the dead, the wounded, and they were afraid. Very much afraid of leaving this world.

The Virus cut Awayun Learning

Wilder Allui Ukuncham does not have this name before the Peruvian State. His national identity card (DNI) shows the name Wilder Gómez Ukuncham, a 26-years-old male. The reason for this confusión comes from the registry of his ancestors living in the Marañon River basin. His maternal grandfather, Mayán Allui, had no studies, as did his brother Eduardo. When Eduardo got an ID card, he changed his surname thinking that his children could be embarrassed of their indigenous origins”, narrates the young artist. “This is why he choose Gómez, an apach name”.

One day, when his great uncle [Eduardo Gómez] decided to register his children in the city, Wilder Allui’s father asked him to register him as one of his children. He wanted to have a DNI to obtain benefits from the Peruvian State. So, when Wilder was born, his father registered him with the name that appeared in his DNI. Wilder inherited this apach name, but he mentions that for his community he will always belong to the Allui lineage.

Rio Soritor, where Allui lives, belongs to the Awajun people, also known as aguaruna. With a strong warrior tradition, it is the second most numerous people in the Peruvian Amazon. It is mainly located in Amazonas, and extends to the north of San Martín, Loreto and Cajamarca.

The Ministry of Culture indicates that the population of the Awajun communities consists of 65,828 people. However, the pandemics has snatched many lives. According to the situation room for indigenous peoples of the Ministry of Health (Minsa) updated to July 14, 2021, the Awajun people is the most affected by the pandemic and reports 7,442 (cases). Of these figures, 1,755 cases are located in the San Martín region, 166 in the Awajun district where Allui lives. In his community, Rio Soritor, the Government estimates only 5 confirmed cases, but he assures there are many more.

The same Minsa source, updated to July 14, 2021, indicates that 142 Amazon indigenous people have died, of which only 10 would belong to the San Martin region. Allui does not believe in these figures, because he has seen many elders in and around his community die. This, as he mentions, has been the largest impact of coronavirus: take away most of the wisemen in town. These are called muun in their language and are kakajam (strong, brave), who taught boys and girls about their ancestors and the Awajun culture. When they die, Allui tells us, they leave this transmission of learning halfway. “That is our great loss. They could not transmit their great knowledge; they took it to their graves”.

NEW DISEASE. The Awajún ceramist Sekut Peas Tuits makes pots in which prepares infusions of kion and other herbs to relieve the discomfort of the disease they called iinia chicham.

NEW DISEASE. The Awajún ceramist Sekut Peas Tuits makes pots in which prepares infusions of kion and other herbs to relieve the discomfort of the disease they called iinia chicham.The muun were the first to be affected by the coronavirus. As they fell ill, they stopped going to the farm (chacra). They did not plant bananas or yucas anymore; neither did the hunt in the forest. Soon they ran out of food and money they obtain from selling their agricultural products to the apach. “The suffering of the community started like this”, remembers Allui, who points out that when the wisemen left, the young people like himself felt like orphans, all by themselves. “The community remained in silence.”

The muun were followed by female leaders and young men. Everyone got this invisible virus. "Life became difficult," says Allui. The change was noticeable in everyday life: the men were easily tired, they could not work in the farms as before, they used to plow the land until sunset and, without any rest, they fished in the river with hooks. When they got home, they drank cold water.

"Nobody does that anymore," Allui regrets. They cannot pick coffee in the rain because their chest hurts, and they get tired quickly. “Before, they worked in the rain, they fished in the rain, they went hunting at night,” he recalls. But now, if they go out into the field, they immediately feel dizzy. They cannot drink cold water or bathe in cold water. “We have stopped being what we used to be; we have become other people”.

He believes that the transformation began the first week of July 2020. At first, they were only rumors of a disease that hit neighboring communities. Allui was worried because he didn't know how it would attack him, until it happened. He first he felt a strong pain in the eyes, blurred vision, chills, headache, fatigue, and high fever. "I thought I would die, because they said there was no cure," he tells us.

During that period, his parents, brothers, and friends cared for him like a child. They had already overcome the disease and were not afraid of catching it again. They prepared hot drinks with medicinal plants from the forest: kaip (Petiveria alliacea L.), ajeg (ginger), chuchuhuasi and sanango. These remedies were combined with steam baths based on medicinal plants, which took away the fever and headaches. Only the chills remained, which he was able to overcome by resting.

Art to Save Awajun Memory

Wilder Allui says that he has been drawing since he was in his mother's womb. To support this, he explains that he was predestined to be an artist, that he carried it in his blood and in his hands. “From a very young age I would hold pencils and draw. I was already thinking about painting since he was a baby, ”says the young artist who has captured the arrival of the coronavirus in his town and the fight against the disease, in a painting that accompanies this article.

DRAWING AND RESISTING. "By painting I give strength and life to our culture, to our forest," says Wilder Allui, from his community located in the Soritor river basin in the San Martin region.

DRAWING AND RESISTING. "By painting I give strength and life to our culture, to our forest," says Wilder Allui, from his community located in the Soritor river basin in the San Martin region.As is often the case in art, Allui's beginnings were not easy. He did not have a teacher in this field; he only remembers that he used to go to the forest, fell in love with a bird and ran home to draw it on some notebook sheets. He doodled, but he was not discouraged because "if something is for you, you love it and you cannot leave it, even if others say no to you."

When he entered the first year of secondary school, he met professor Abraham, a teacher who used to paint and who became a guide for Allui. "I wanted to paint like him, so when class was over, I ran home to imitate his drawings," says the Awajun painter. At that time, he did not care about the meaning of what he did; the rhythm of pencils and tempera just flowed.

But things got complicated and he stopped studying at 14. He went to Chiclayo to work and, three years later, he returned to Rio Soritor. The first person he met was Professor Abraham, who surprised at seeing him said some words that encouraged Allui. "You have a talent for art, I'm going to teach you, but finish studying." Later, one day after he had finished secondary school, he wondered who he was, while painting. “I'm an artist,” he told himself.

Since then, he has not left art for a single day. On some occasions, he turns to ayahuasca for inspiration. This a plant called datem in Awajun is traditionally used in the Peruvian Amazon to dive on a spiritual journey. On this occasion, the result was a painting that displays in detail the struggle of the Awajun people against the coronavirus, represented by a red-eyed skull that expels threads of blood into the forest and its creatures.

Nearby, an indigenous Awajun wearing a mask is holding onto an ayahuasca tree that emits a yellow light, like a protective shield. Behind the man stand long trees with the faces of animals, who are watching the virus expectantly. One of the branches of these trees ends in a spear, the symbol of the fierce defense of plants against SARS-CoV-2.

The image was conceived in the middle of Allui's journey. "All that was shown to me by ayahuasca, which is waimatai (the way, in Awajun)," says the painter. In the ayahuasca-induced dream, Allui was standing in the middle of the forest and looking for the virus. "I did not know what it looked like, I did not know its face; I only remembered that this disease advances like the wind, until its face appeared." When he came back, he began to trace without stopping. All he did was to follow the route of his own dream.

As on this occasion, Allui's source of inspiration has always been the nature that surrounds him. He became a painter by drawing the Rio Soritor forest, the wild animals, capturing the spirit of the plants. Now, he affirms, he is only recording, with his traces, a piece of a tragic story, but also a story of "resistance, of the fight of our medicinal plants against a mortal enemy."

It is because of these plants, points out says Allui, they were able to defeat the coronavirus, and they have returned, little by little, to their usual tasks in Río Soritor. Currently, he is working with some artisans in the community, who make accessories with natural seeds. The next step will be to build an exhibition and sale center for these products. Besides, Allui translates from Awajun into Spanish, paints and writes poems and songs with themes based on the Amazonian indigenous world.

COMMITMENT. Awajún artist says he also wants to combat the lies surrounding the pandemic and vaccination with his paintings.

COMMITMENT. Awajún artist says he also wants to combat the lies surrounding the pandemic and vaccination with his paintings.Now he captures not only the natural world of his community, but also the problems it is going through. Allui believes that art is a vehicle for change. "I thought about what I could do from where I am, and I discovered that I can give an alert with my paintings," he says. I would like my community to wake up and to speak up”. The Awajun artist lists the tragedies that haunt his people: rape of minors, invasion of land by the apach, corruption, illegal mining.

But there are other mistakes that he also observed during the pandemic, such as the State issuing bonds in the cities. “Even the sick got out of bed to collect their money. They have been a great source of infection”, he indicates. More worrisome, however, is the avalanche of misinformation surrounding vaccines. He has heard that the antigens have been created to exterminate the indigenous people, to strip them of their lands and give them to the apach. "They say that the apach have their own vaccine and there is a different one for the innia (Awajun)."

He wants to combat all this with art, through his paintings. Allui knows that, like the power of the forest plants, he also has a powerful weapon, capable of transforming his community. "By painting I give strength and life to our culture, to our forest." So, he wants to give back to nature the gift she gave him by endowing him with art.